A banking crisis in the U.S. financial system began with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) on March 10th, the first large bank fall since Washington Mutual’s collapse during the 2008 global financial crisis. SVB’s failure resulted in a state of panic in the sector, as depositors rushed to withdraw their money and many bank stock values experienced record losses. Within two months, SVB’s failure was followed by the collapse of Signature Bank, the European Credit Suisse, and First Republic, costing regulators billions of dollars in rescue schemes and wiping out three of the largest U.S. banks and the second-largest Swiss Bank.

In the intricate web of global finance, banks serve as the pillars that support economic stability and growth. The very nature of banking is largely misunderstood and often vilified by the popular press when problems occur. Talking heads are shocked to discover the structure of borrowing short-term (deposits) and lending long-term (mortgages). The added advent of a social media driven run on SVB underscores how few understand the business and how quick those same groups are to create turmoil in it.

This doesn’t mean there are no problems. Despite constant reassurances by regulators since the 2008 crisis that the resilience of banking sectors in advanced economies was guaranteed by strengthened and improved regulations, the current collapse resulted from poor and inadequate application of those regulations. As well, poor risk management, mismanagement, excessive risk-taking, and misunderstanding of Federal Reserve policy all contributed to these banks’ demise.

This article will discuss the current banking turmoil, explain the mechanics and explore the causes, consequences, and regulatory responses to a crisis that has sent shockwaves through the financial landscape.

The Mechanics of Modern Banking: How Banks Work?

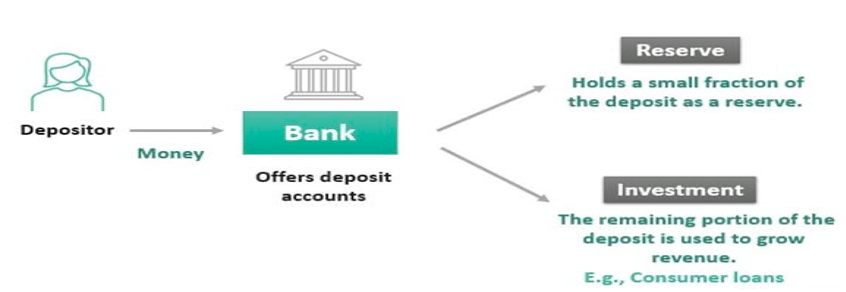

In general, banks operate as financial intermediaries, connecting those with excess funds (savers) to those in need of funds (borrowers) in a complex web of transactions and services. At their core, banks accept deposits from individuals and businesses, which form the foundation of their lending activities. These deposits are then used to provide loans and credit to borrowers, enabling them to finance various ventures, such as purchasing a home, starting a business, or funding large-scale projects. In addition to lending, banks offer a range of services, including payment processing, investment management, and wealth advisory. They also generate revenue through interest earned on loans and investments, as well as fees charged for their services. The idea is that the return from investments should be higher than the return on deposits, creating an interest rate spread that would result in the bank’s profitability. Two important features that characterize the modern banking system and that play a main role in their risk-return dynamics are fractional-reserve banking and maturity transformation.

First, Fractional-reserve banking (FRB) implies that only a fraction of bank deposits would be available for withdrawal in a given day, allowing the bank to invest or lend the rest of the money to generate return, instead of keeping it idle. By using a portion of deposits for investment, banks do not need to hold huge amounts of capital, freeing up capital for investment and fostering economic growth. On the other hand, the FRB system has been accused of increasing the threat of bank runs. Given that banks hold only a fraction of deposits, under stressful situations, they might run into liquidity troubles if depositors rush to withdraw their money simultaneously, which by itself could cause panic and lead to further massive withdrawal demands (aka a bank run). Figure 1 below illustrates the FRB mechanics.

Figure 1 – The Mechanics of Fractional Reserve Banking

Source: Economist Robert Murphy

Second, maturity transformation is basically borrowing short-term and lending long-term. By default, banks’ deposits have a short-term nature as customers would want to access their cash when needed, while their assets and credit tend to have a longer-term nature. Maturity transformation provides a key economic function, as it allows banks to optimally choose higher returns on their assets, increasing their net interest margins and encouraging them to provide credit to foster economic growth and investment. Yet, maturity transformation makes liquidity and duration risks inherent components of the banking sector, as depositors might wish to withdraw their funds in a timeframe that misaligns with the bank’s investment maturities.

Deposit insurance is often provided by regulators to mitigate the risks of bank runs arising from the FRB system. Moreover, deposit insurance as well as risk management, especially of maturity mismatch, would form a crucial part of the bank’s sound management. In the U.S., the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insures all deposits of up to $250,000. While this might help, as will be explained later in the article, it has proved to be insufficient during the recent collapse of SVB and other banks.

What Can Cause a Banking Crisis?

Several key factors can contribute to the onset of a banking crisis. One common cause is excessive risk-taking and poor lending practices by banks, such as extending loans to borrowers with weak creditworthiness or engaging in speculative investments. Inadequate risk management, including insufficient capital buffers and flawed risk assessment models, can also amplify the vulnerabilities within the banking system. External shocks, such as economic downturns, sharp asset price declines, or sudden changes in market conditions, can trigger a banking crisis by exposing the weaknesses and vulnerabilities of financial institutions. Furthermore, regulatory failures, lax oversight, and inadequate supervision can create an environment that fosters risky behavior and allows imbalances to accumulate within the banking sector. By identifying and addressing these risk factors, policymakers can work towards safeguarding the stability and resilience of the banking system, thereby reducing the likelihood and severity of future banking crises.

A banking crisis is a severe disruption in the stability and functioning of the banking system, often resulting in the failure of financial institutions and significant economic repercussions. Taking the mechanics of how banks work into consideration, experts have generally classified the causes of banking crises into two categories: (1) depositor panics or bank runs, and (2) widespread losses in the bank’s assets.

First, during a bank run massive deposit withdrawals can cause illiquidity at banks that are fundamentally solvent. This might cause the bank to sell its assets, often at a discount, to increase liquidity, which might render the bank insolvent and lead to more panic, as depositors question the bank’s stability. Even in situations when a bank’s performance is sound, bank runs can be self-fulfilling prophecies, as depositors fear that others will also withdraw their money, causing them to rush into an undue bank run.

Second, banking crises are often the result of intense losses in banks’ assets, which cause insolvency. Those can commonly result from market failures, government interventions, macroeconomic shocks, or fraud. For example, historically, overly expansionary monetary and fiscal policies have caused excessive credit provisions and overinvestment in real assets, increasing the vulnerability of banks to losses in their asset values. Even in cases when investments are in low-credit-risk, currency mismatches, maturity mismatches, and interest rate risks can cause indirect credit risks, resulting in asset-value losses.

As will be explained in the next section, the recent banking failures have been caused by a combination of depositor panics and asset-value losses, arising from a mix of high-interest rate risks, maturity mismatches, excessive investment in government securities, risk mismanagement, and inadequate regulations.

The Current Banking Turmoil: Total Loss and Timeline

The global banking industry has experienced its fair share of turmoil in recent years, with significant implications for economies worldwide. The financial crisis of 2008 exposed vulnerabilities within the banking sector, leading to a wave of bank failures, government bailouts, and economic downturns. Since then, the industry has undergone substantial regulatory reforms aimed at enhancing stability and preventing the recurrence of such catastrophic events. However, even with these measures in place, the banking sector continues to face challenges and periodic disruptions.

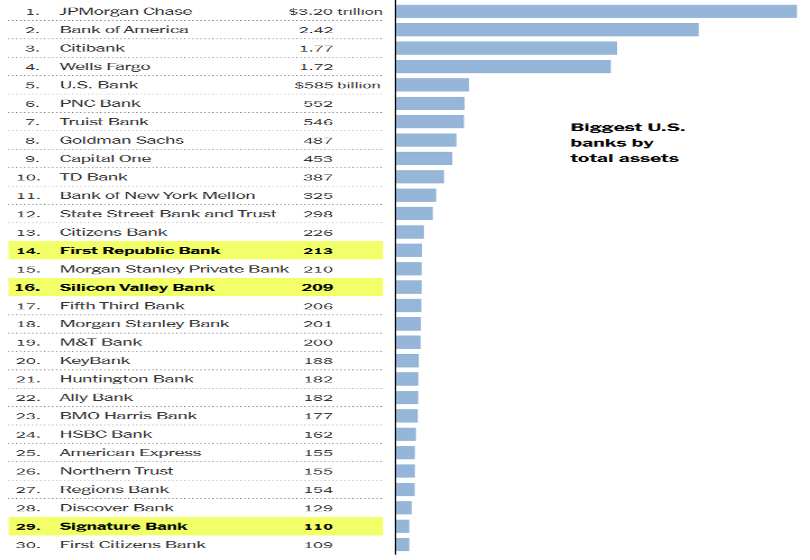

Since March 2023, three of the largest U.S. banks and one large European bank have collapsed, marking the largest banking failures since the 2008 financial crisis and leading to fears of a broader-industry fallout. SVB, Signature Bank, and First Republic were among the 30 biggest U.S. banks (Figure 2) and Credit Suisse was the second-largest Swiss bank by total assets.

The timeline of these events reveals a domino effect, as one bank’s collapse can trigger a ripple effect across the industry, leading to a loss of public trust and potential economic instability. It is crucial to closely monitor and understand these developments to ensure the long-term viability and health of the banking sector.

Figure 2 – The Biggest U.S. Banks by Total Assets

Source: The New York Times.

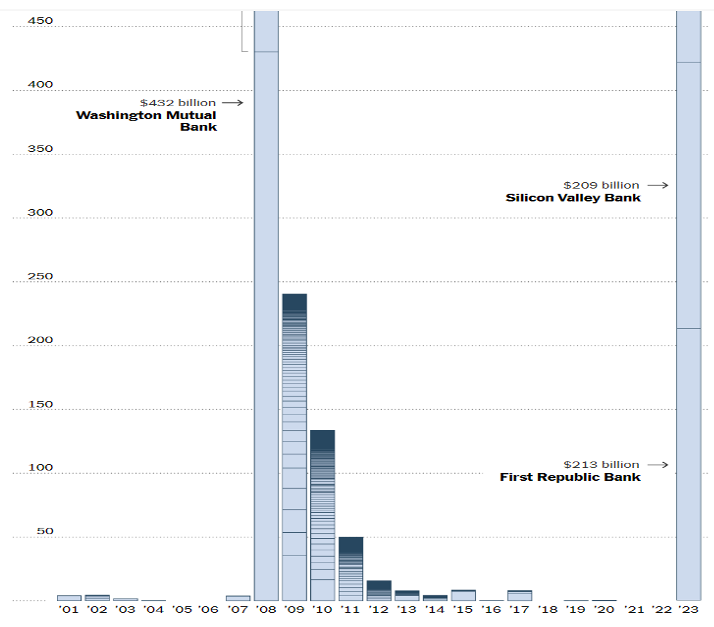

Adjusted for inflation, the three failing U.S. banks held a total of $532 billion in assets, higher than the $526 held by the 25 banks that collapsed during the global financial crisis in 2008 (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – U.S. Bank Failures Sized by Total Assets, by Year and Adjusted for Inflation

Source: The New York Times.

Below is a timeline of banking failures that started in March 2023, from the collapse of SVB to First Republic Bank.

- February 24: Just two weeks prior to SVB’s collapse, KPMG signs off SVB’s auditing report, giving the bank a clean bill of health.

- March 08: SVB announces that it sold $21 billion worth of bonds, booking $1.8 billion in realized losses, and that it plans to raise $2.25 billion by selling stocks to meet depositors’ withdrawal demands. A few hours later, Moody’s downgraded SBV to Baa1 from A3.

- March 09: SVB’s stock crashes, losing 60% of its value and triggering a market-wide decline. On that day, Dow fell more than 500 points and the four largest U.S. banks (JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Citigroup) lost $52 billion in market value. As fear heightens, venture capitalists (VCs) and startups rush to withdraw their deposits from SVB, resulting in $42 billion in withdrawals over the course of the day.

- March 10: After losing 69% of its stock value, SVB’s shares are halted and the FDIC takes control of the bank, marking the second-biggest bank failure in U.S. history and the first since 2008.

- March 12: a second massive bank failure follows as Signature Bank is taken over by the FDIC. As depositors panic over their locked SVB and Signature Bank accounts and over fears of a broader bank run, regulators announce emergency measures reassuring that all depositors at both banks would get their money back.

- March 13: First Republic Bank becomes at risk as its shares drop by more than 60%.

- March 15: In Europe, Credit Suisse Group’s stock drops by 24% and the bank announces its plan to borrow up to $53.7 billion (50 billion Swiss francs) from the Swiss National Bank to increase its liquidity. Other European banks are also hit, including Société Générale (France), BNP Paribas (France), and Deutsche Bank (Germany).

- March 16: The Federal Reserve announces that 11 of the largest U.S. banks have injected $30 billion of deposits in First Republic.

- March 17: First Republic shares plunge to a record low despite market infusions, taking the loss to 70%. Credit Suisse shares also drop, despite borrowing money from the Swiss National Bank.

- March 19: UBS Group acquires Credit Suisse for over $3 billion.

- April 07: First Republic announces that it will suspend its quarterly cash dividend payments on preferred stocks, increasing share losses to reach 90% since the start of March

- April 24: First Republic discloses $100 billion worth of deposit withdrawals during March.

- May 01: The FDIC seizes First Republic and signs a deal to sell it to JP Morgan Chase.

The Collapse of SVB: What Really Happened?

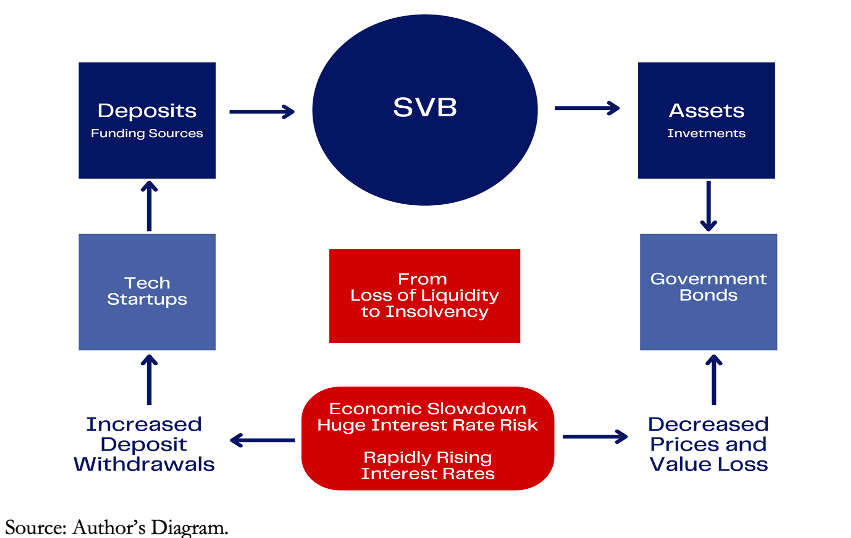

On March 10, the collapse of SVB shocked the market, resulting in a classic bank run and several other bank failures. So, what really happened? The immediate cause of the failure was a loss of liquidity. As depositors massively rushed to withdraw their money and draw down their accounts, it wasn’t long before the bank ran out of liquid cash to meet such cash demands. But at the core, the collapse was the natural consequence of a concoction of reasons, including weak regulations, mismanagement, excessive risk-taking, rapid deposit and credit growth, and a huge interest rate risk. Figure 4 summarizes the mechanisms of the SVB collapse.

Figure 4 – The Mechanics of SVB’s Collapse

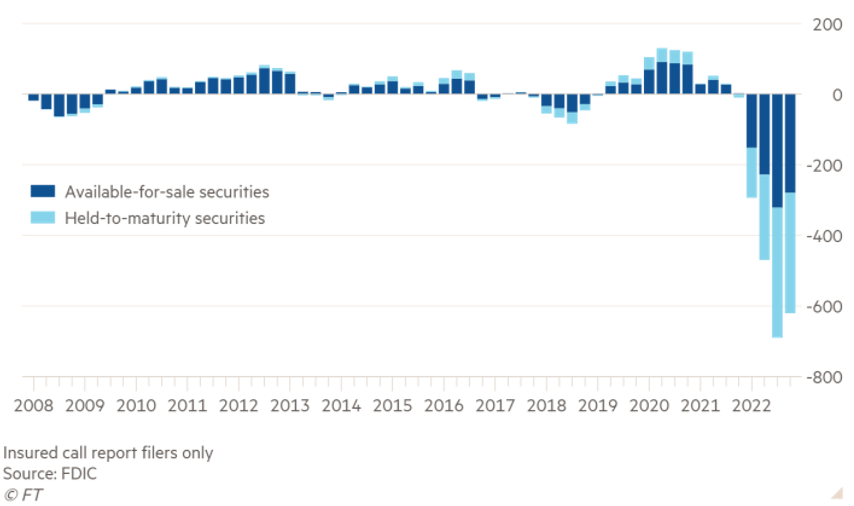

On the asset side, a large proportion of the bank’s deposits were invested in assets that have massively lost their value over the past year; a situation that was caused by the Federal Reserve’s aggressive interest rate hikes and quantitative tightening. Most of SVB’s deposits were invested in long-term fixed-rate government bonds, which are usually the safest risk-free bonds to purchase given the low likelihood that the government will default. However, when interest rates sharply increased over the past year including the long end of the yield curve, the prices of such bonds rapidly went down. So, while SVB now had to pay higher interest rates on its short-term deposits, it could only sell its government bonds at discounts (losses) to their face value. In total, U.S. banks are estimated to have incurred around $620 billions of unrealized losses on their books, resulting from low-yielding bond investments, by the end of 2022 as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – U.S. Banks Unrealized Gains (Losses) on Investment Securities, $billion

Source: Financial Times.

On the liability side, the unique nature of SVB’s customer base largely contributed to the debacle. First, most of SVB’s depositors were start-ups and tech companies (e.g., Roku which had around $487 million deposits in the bank). In the wake of the rising interest rates and economic slowdown, such companies have been struggling to achieve profits and receive additional venture capital funding. As a result, these depositors’ cash demands were increasing, requiring SVB to provide immediate liquidity Second, startups are highly influenced and funded by a group of VCs, who can rapidly push them to withdraw deposits at scale if they see looming risks. Third, what made matters worse was the particularly high ratio of uninsured deposits in SVB, accounting for a share of more than 85% of total deposits While the FDIC insures deposits of up to $250,000, many of the startups had millions or even hundreds of millions of dollars in their accounts, which exacerbated the risk perception and led to panic.

What was truly unique to SVB was the advent of the social media driven bank run. A group of professors wrote a research paper on this new wrinkle to an old problem. They concluded that “Social media fueled a bank run on Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), and the effects were felt broadly in the U.S. banking industry. (They) employed comprehensive Twitter data to show that preexisting exposure to social media predicts bank stock market losses in the run period even after controlling for bank characteristics related to run risk (i.e., mark-to-market losses and uninsured deposits). Moreover, we show that social media amplifies these bank run risk factors.”

Eventually, SVB was unable to meet its cash requirements, necessitating it to sell its government bonds, at which point its unrealized losses became realized. The tipping point came when the bank announced on March 8 that it had sold $21 billion worth of its bonds, revealing $1.8 billion in realized losses, and that it would have to raise $2.25 billion capital to meet the depositors’ withdrawal needs; a move that was perceived as “unnecessary” by experts, especially as SVB had sufficient capital to address the issue without causing widespread hysteria. It wasn’t long before the announcements triggered a panic of withdrawals, pushing down SVB’s stock value by over 60% and resulting in losses of over $80 billion in bank shares.

The collapse of SVB serves as a cautionary tale, emphasizing the critical importance of robust risk management, prudent lending practices, and effective regulatory oversight to ensure the stability and resilience of the banking system as a whole. It also highlights the need for banks to proactively adapt to changing market conditions and anticipate potential risks in order to safeguard their long-term viability and protect the interests of depositors, shareholders, and the broader economy. Finally, it highlights a need for a bank rapid response squad to meet negative social media and mitigate the negative posts with education and facts.

More U.S. Bank Failures Follow: Signature Bank and First Republic

Just two days after SVB’s collapse, market panic pushed Signature Bank to its demise, marking the third-biggest bank failure in U.S. history. After the fall of SVB on March 10, fear pushed depositors to withdraw more than $10 billions of their cash at Signature Bank. On March 12, the FDIC announced that it would take over the bank to protect depositors and the stability of the banking system.

According to board member Barney Frank, the take-over of Signature Bank was unexpected and came as a surprise to its executive. Despite the post-SVB panic, managers have explored all means to mitigate the situation. While by March 12, the situation started to stabilize and the withdrawal streak had slowed down, according to Frank, regulators proceeded to seize the bank. There was no real objective reason for the collapse, he stated, “I think part of what happened was that regulators wanted to send a very strong anti-crypto message… We became the poster boy because there was no insolvency based on the fundamentals.”

Nevertheless, according to the FDIC, Signature Bank’s operations were halted due to poor management as the bank did not fully appreciate the risk associated with its volatile funding sources. While the source of SVB’s volatile deposits came from cash-tight tech startups, Signature Bank mainly served crypto companies, with around $16.5 billion in deposits from digital-asset-related customers (comprising more than 20% of total assets).

On May 1, the collapse of First Republic marked the third bank failure in two months, and the largest bank to fail since the 2008 financial crisis as it surpassed SVB and Signature Bank in total asset size. Following the earlier bank collapses, First Republic lost $100 billion in deposits last March, pushing the largest U.S. banks to inject $30 billion to try to save it. Similar to the other two banks, the majority of First Republic’s deposits were above the $250,000 deposit-insurance limit, which fed the depositors’ panic and led to the withdrawal rush. Almost 68% of the bank’s deposits were uninsured. Moreover, First Republic had an abnormally high liability-to-deposit ratio of around 111%, implying that it lent more money than its deposits, which particularly increased its risks.

Following a competitive bidding process, First Republic was seized in a deal between regulators and JP Morgan Chase to buy the bank, assuming the majority of its $229.1 billion assets and all of its $103.9 deposits. According to the deal, the FDIC and JP Morgan Chase agreed on a loss-sharing scheme, with the FDIC incurring a cost of around $13 billion to fund a deposit insurance fund.

Contagion Reaches Europe: The Fall of Credit Suisse

Following SVB’s collapse on March 10, European banks’ stocks started ailing as contagion reached Europe. Credit Suisse was the one to bear the brunt. Credit Suisse’s end came on March 19, when UBS acquired it for $3.2 billion (3.0 billion Swiss francs) in a deal with Swiss regulators to contain contagion and prevent a banking crisis. According to the Swiss National Bank, “With the takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS, a solution has been found to secure financial stability and protect the Swiss economy in this exceptional situation.” The deal allowed UBS to maintain its shareholder’s power as the terms provided a single UBS share for every 22.48 Credit Suisse shares held by the latter’s shareholders.

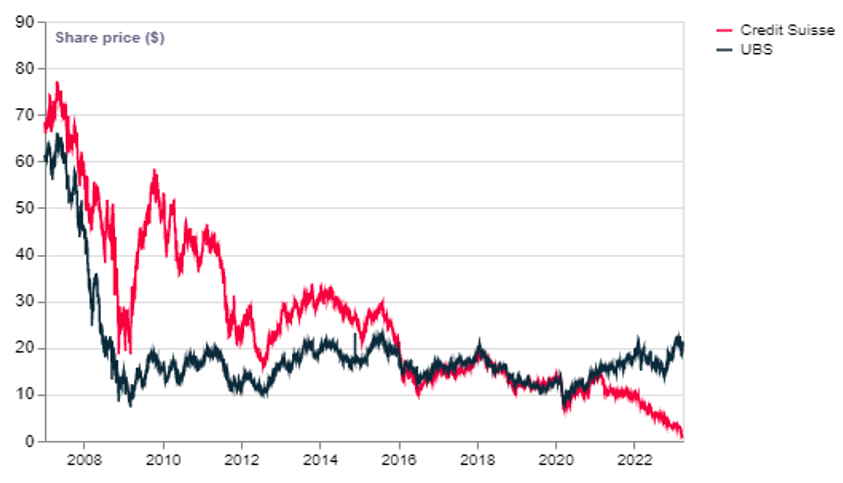

While the collapse of U.S. banks might have triggered the panic that led to Credit Suisse’s collapse, the bank has been struggling with a number of scandals for quite some time. In recent years, the bank’s employees have been investigated, fined, and even imprisoned for allegations of corruption, tax evasion, money laundering, and corporate espionage. In October 2022, following a Swiss journalist’s tweet that a “major international investment bank is on the brink,” several investors assumed that such bank was Credit Suisse, leading to deposit withdrawals of more than $107 billion (100 billion Swiss francs) and a sharp decline in the bank’s stock price (Figure 6).

Figure 6 – Credit Suisse and UBS Share Prices

Warning Signs and Red Flags: Misleading Regulations and Poor Management

Following the collapse of SVB’s, the Federal Reserve conducted an investigation into the collapse and published a report on it on April 28, 2023. According to the report by the Federal Reserve, the failure of SVB can be attributed to the following four causes:

- Risk Mismanagement: “SVB’s board of directors and management failed to manage their risks.” This oversight exposed the institution to vulnerabilities that ultimately led to its collapse.

- Poor Supervision: “Fed supervisors did not fully appreciate the extent of the vulnerabilities as SVB grew in size and complexity.” This lack of awareness hindered timely interventions that could have addressed the emerging issues.

- Inadequate Action by Supervisors: “When supervisors did identify vulnerabilities, they did not take sufficient steps to ensure that SVB fixed those problems quickly enough.” The failure to act swiftly further exacerbated the situation.

- Looser Regulations for mid-sized Banks: “The Federal Reserve Board’s response to a 2018 law—the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, which lightened the oversight of some mid-sized banks—and the shift in top Fed policymakers’ guidance to supervisors impeded effective supervision by reducing standards, increasing complexity, and promoting a less assertive supervisory approach.” This compromised the oversight process.

The recent streak of bank collapses came despite the continued reassurances by regulators, central banks, and rating agencies the stronger regulatory and supervisory regimes put in place since the 2008-2012 financial crises should guarantee the resilience of banking systems in advanced economies. In January 2023, just two months before the fallout of SVB, the International Monetary Fund reassured that “Financial sector regulations introduced after the global financial crisis have contributed to the resilience of banking sectors throughout the pandemic, but there is a need to address data and supervisory gaps in the less-regulated nonbank financial sector.” Yet, the supposedly resilient and well-regulated banking sector was hit head-on.

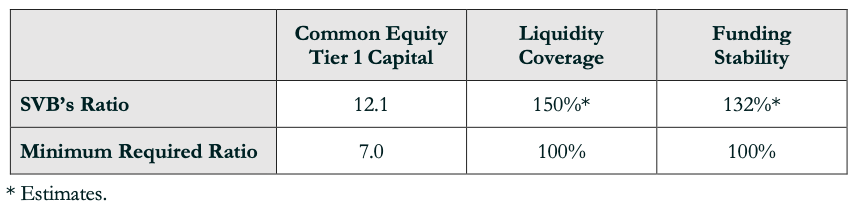

Following the 2008 global financial crisis, discussions led by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision focused on strengthening three potential balance-sheet fragilities; capital adequacy, adequate liquidity, and a net stable funding ratio. As shown in Figure 7 below, SVB easily passed all the regulatory requirements on paper.

Figure 7 – SVB Would Have Passed the Minimum Regulatory Requirements

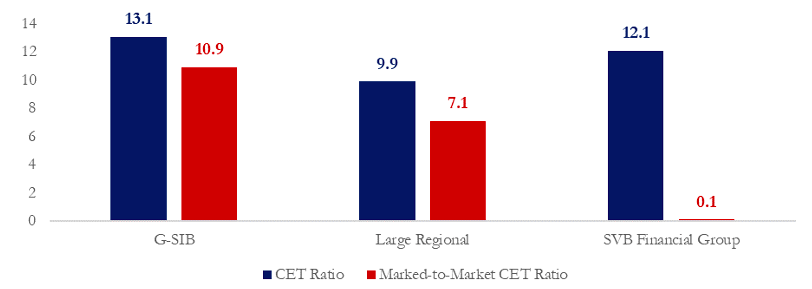

- Capital Adequacy: new regulations necessitated banks to maintain adequate levels of equity (capital) buffers, to hedge depositors and creditors against risks and assets losses. According to the Federal Reserve, large banks’ Common Equity Tier 1 (CET) is required to be at least 4.5% of risk-weighted assets (Basel minimum), in addition to a minimum of 2.5% bank-specific stress capital buffer (based on the Dodd-Frank stress test) and a minimum of a 1% buffer for global systemically important banks or G-SIBs (large significant banks whose failure might trigger a financial crisis). SVB was required to maintain a minimum CET ratio of 7% (the minimum 4.5% plus the 2.5% stress buffer). As shown in Figure 7 below, in the fourth quarter of 2022, SVB Financial Group would have passed its CET ratio requirement with flying colors as it maintained a 12.1% ratio, well above the large regional banks, and almost on par with G-SIB banks. However, such strong capital performance proved to be misleading. The Federal Reserve exempted mid-sized banks such as SVB from including unrealized losses in their capital requirements, allowing them to reduce their capital by billions of dollars, giving a false impression of strong capital performance. Indeed, according to an analysis by Moody’s, when accounting for SVB’s unrealized losses and asset fair value, its marked-to-market CET ratio significantly dropped (Figure 8).

Figure 8 – Common-Equity Tier 1 Ratios for SVB and other Bank Groups, 2022 Q4, %

Source: Moody’s Analytics.

- Liquidity Coverage: regulations required banks to comply with a minimum liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), necessitating them to maintain sufficient high-quality liquid assets that would fully cover potential cash outflows under stress. For the largest banks, the LCR should cover 30 days of stress. A pitfall, however, is that the Federal Reserve eases such regulations for mid-sized banks as SVB, relaxing the stress assumption by multiplying the projected net cash outflows by 70%. This relaxation compromised the effectiveness of the LCR assessment for such banks. Accordingly, SVB would have probably passed all the LCR requirements. It is estimated that in the fourth quarter of 2022, SVB had a 150% LCR, higher than the required 100% minimum.

- Funding Stability: regulations required banks to maintain a net stable funding ratio (NSFR), which requires the bank’s available stable funding to at least cover its required stable funding over a 12-month period. While the numerator or available stable funding is determined by the quality of deposits (e.g., whether it’s insured, operational, and characteristics of the depositor), the denominator or required stable funding largely depends on the quality of the bank’s assets. The NSFR complements the LCT, with the latter focusing on the quality and liquidity of the assets (investments) and the former on the quality and stability of liabilities (funding sources). Again, SVB would have easily passed its NSFR requirements, as it is estimated to have maintained a 132% ratio, compared to a global NSFR average of 120% and a minimum requirement of 100%. Yet, two pitfalls were missed by managers as well as regulators. First, most of SVB’s uninsured deposits were from VC-funded startups, which often ran negative cash flows, especially during the current economic downturns. Second, most of SVB’s held-to-maturity government securities were considered high-quality despite the increasing interest rates and fall in prices.

So, although on the books SVB’s performance was pristine, mismanagement and inadequate regulations (especially for mid-sized banks) missed the warning signs. Despite the adequate capital, liquidity, and funding ratios, the rapid growth of uninsured deposits, the concentration of deposits in a single sector of volatile customers, and the concentration of investments in long-term government securities were all red flags. Indeed, government securities are considered risk-free with no credit risk, yet they were entirely exposed to interest rate risk.

By default, the maturity transformation nature of banks results in assets that are generally less liquid than liabilities/deposits. Accordingly, banks will often face a duration risk, which would naturally rise with higher interest rates as the longer-duration assets suffer a disproportionate loss in value. Leslie Lipschitz, economist and former director of the IMF Institute, warned last year that “Tightening Monetary Policy will Put a Hole in the Fed’s Balance Sheet… the Fed does not mark its securities to market these losses would not be realized or shown. However, any sizable sale from this portfolio, presumably of those securities closer to maturity and thus of shorter duration, would force the Fed to realize a loss.” One would then expect that the Federal Reserve takes a cue from its own balance sheet risks and reflects it on the naturally more vulnerable deposit-taking banks.

How Did Regulators Respond to the Banking Crisis and How Much Did It Cost Them?

During times of banking crises, regulators play a pivotal role in restoring stability and rebuilding confidence in the financial system. In the aftermath of the recent banking turmoil, regulatory bodies implemented a range of measures to address the underlying issues and prevent future systemic risks. In the U.S., the Federal Reserve responded quickly to the collapses of SVB and Signature Bank by lifting the $250,000 deposit-insurance limit for both banks to reassure depositors and mitigate the risk of a sector-wide bank run. In addition, the Federal Reserve has provided further assistance to banks to help mitigate the spread of bank failures. In other words, it has exercised its lender-of-last-resort function, providing loans to banks as a source of liquidity to meet depositor demands under stress.

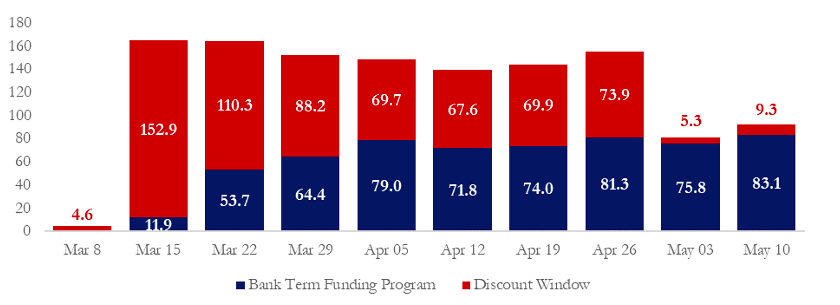

In March, the Federal Reserve announced a Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), which provides loans to banks and other deposit-taking institutions to meet their depositors’ demands. Offered loans are for up to a year with an interest rate equivalent to 0.10 percentage points above the one-year overnight index swap (OIS) rate (currently at 6.62%). In return, the banks would pledge collateral, such as securities and other qualifying assets, which would be valued at par. As of May 10, banks have borrowed a total of $83.1 billion through the BTFP.

Another facility that the Federal Reserve offers is the Discount Window, which offers cash loans to banks for only a few days or weeks. While banks still pledge collateral in return, unlike the BTFP, such assets are valued at market rather than face value. As of May 8, the interest rate on such short-term loans was set at 5.25%. Banks’ borrowing at the Discount Window reached $152.9 billion on March 15 (from $4.6 billion on March 9), before falling to $73.9 billion on April 26, being offset by more BTFP borrowing. On May 3, borrowing at the window significantly dropped to $5.3 billion, however, such a drop was the result of the Federal Reserve moving its loans to First Republic under another category on its books (reflecting banks that have been seized by the FDIC. Figure 9 presents the total borrowings under the BTFP and the Discount Window between March 8 and May 10.

Figure 9 – Federal Reserve’s Exceptional Lending, $billion

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

In guaranteeing deposits, providing emergency loans, and bailouts, the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and the U.S. banking industry have incurred costs of around $400 billion to protect the system and support cash-short banks. Those include:

- $212.5 billion credit extensions by the Federal Reserve to the seized banks, including guaranteeing all deposits, as of May 10.

- $83.1 billion under the BTFP lent to banks, as of May 10.

- $9.3 billion lent by the Federal Reserve to banks at the Discount Window, as of May 10 (down from $153 billion in March).

- $50 billion financing from FDIC to JPMorgan Chase to acquire First Republic.

- $13 billion deposit insurance fund by the FDIC to share First Republic losses.

- $30 billion injection by U.S. banks to rescue First Republic

Similarly, in Europe, the cost has been high as the Swiss National Bank was eager to bail out Credit Suisse and ensure that the UBS deal goes through. Costs included:

- $54 billion (50 billion Swiss Francs) emergency loan to Credit Suisse.

- $225 billion (209 Swiss francs) to UBS in Swiss-state-guaranteed loans and protection against potential losses.

While regulators might have prevented a widespread banking crisis by guaranteeing deposits and providing loans to banks, experts have criticized the move, arguing that it could encourage bad investor behavior and excessive risk-taking, raising the question of moral hazard. “This is a bailout and a major change of the way in which the U.S. system was built and its incentives… If all bank deposits are now insured, why do you need banks?” argued Nicolas Veron, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. Moreover, Michael Every and Ben Picton, Rabobank bank strategists, argued that “If the Fed is now backstopping anyone facing asset/rates pain, then they are de facto allowing a massive easing of financial conditions as well as soaring moral hazard.”

Conclusion

The recent banking crisis has served as a stark reminder of the fragility of the financial system and the potential consequences of poor management and misleading regulations. As we have explored in this article, the mechanics of modern banking involve intricate networks of transactions, risks, and dependencies. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial to grasp how banking crises can occur and their ripple effects on the global economy. More importantly, banks and regulators need to educate investors and the public on how banks function and their importance to the economy.

The collapse of SVB, followed by the failures of Signature Bank and First Republic, highlighted the vulnerabilities within the U.S. banking sector. These institutions, once considered stable and secure, succumbed to a combination of factors, including risky lending practices, inadequate risk management, and a failure to adapt to changing market conditions. The contagion soon spread to Europe, with the fall of Credit Suisse exposing further weaknesses in the banking system.

One of the key lessons from this crisis is the importance of identifying warning signs and red flags. Misleading regulations and lax oversight allowed risky practices to go unchecked, contributing to the eventual collapse of several banks. The need for stringent regulations, robust risk assessment frameworks, and independent audits cannot be overstated. Only through proactive measures can we prevent future crises and protect the interests of depositors and investors.

Regulators played a pivotal role in responding to the crisis albeit, with mixed reactions to their approach. Experts argued that by guaranteeing deposits and providing loans to banks, the regulators could encourage bad investor behavior and excessive risk-taking. In other words, there is a moral hazard to always bailout financial institutions as it only encourages risky behavior with no downside.

We agree with the experts on this. The real solution lies in strengthening the regulatory framework rather than simply bailing out banks.While it is true that mismanagement played a major role in the banking turmoil, the crucial issue is that it was missed by regulators. All the failing banks would have easily passed the regulatory requirements and stress tests set forth by regulators for their size. Red flags were obvious, yet regulators were blindsided, missing the explosive asset growth by banks, high rates of uninsured deposits, massive interest rate risk, and low diversity of deposit sources and asset classes in the failing banks. Even if banks were complying with the regulations in place, such warning signs should have triggered more scrutiny by regulators, especially as several experts have warned of banks’ balance sheet risks.

On March 30, President Biden urged regulators to strengthen oversight for mid-sized banks, stating that “the Trump Administration regulators weakened many important common-sense requirements and supervision for large regional banks like Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, whose recent failure led to contagion.” The proposal called for reinstating the rules that were loosened during the previous administration, for large banks that held assets between $100 and $250 billion in value. This would include, among others, reinstating liquidity requirements that were eliminated for mid-sized banks, enhancing liquidity stress testing, conducting annual supervisory capital stress tests, and strengthening capital requirements for mid-size banks including the treatment of unrealized losses.

Finally, the recent banking crisis serves as a wake-up call for the entire financial industry. It is imperative that banks and regulators learn from past mistakes and adopt measures to mitigate risks, enhance transparency, and strengthen the overall stability of the banking system. The repercussions of a banking crisis are far-reaching, affecting not only the financial institutions involved but also the livelihoods of individuals, businesses, and the broader economy.