What happened and what does it mean for business?

The Fed met and decided to leave interest rates unchanged at +0.25-0.50%. The Fed indicated strongly they would consider raising interest rates in the near term should economic conditions warrant it. In their announcement, they said, “The Committee judges that the case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened but decided, for the time being, to wait for further evidence of continued progress toward its objectives.”

Three members voted to raise interest rates immediately: Kansas City Fed President Esther George, Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester and Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren In their projections for rate hikes in the future, 14 out of 17 projections had a 25 basis point rate hike in December. It should be noted that this is an election year; the central bank has a habit of not acting on interest rates in the meetings leading up to November.

Immediately after the announcement, the stock market rallied, the bond market rallied (yields lower) and the US dollar weakened.

For business, this means that US interest rates will likely continue their slow upward trajectory. The Fed is acting in a very restrained manner given all of the reasons above. Accordingly, we can probably look forward to a slow increase for both the cost of capital and the demand for corporate bond issuances as investors continue to search for yield. As well, the Fed is likely to tolerate for some time an acceleration of inflation and wages before it acts to tamp both down.

The Federal Reserve is said to have a dual mandate of employment and price stability. The Fed actually has another less publicized one: financial market stability. The Fed is a regulator and needs to ensure the safety of the financial system. By keeping interest rates lower for longer, the central bank risks financial bubbles forming in sectors impacted by low rates, among them, the real estate and stock markets. Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren referred to that risk recently when he made the case for raising rates to head off financial instability despite the fact that this would probably slow the Fed’s progress toward its goals of fostering job growth and 2% inflation—an unusual statement of the cost-benefit trade-offs (WSJ).

“A failure to continue on the path of gradual removal of accommodation could shorten, rather than lengthen, the duration of this recovery,” he said.

And this could be the biggest risk for business.

How did the Fed get here?

The central bank has been on hold since December of 2015, but some of its members have been commenting recently that the current economic data supports another rate hike soon. Remember, the Fed has been attempting to normalize interest rates away from the zero rates enacted during their emergency monetary policy after the Great Recession under Chairman Ben Bernanke. The Bernanke-led Fed took interest rates to zero and expanded its balance sheet from $800B to $4.3T to stimulate the US economy. Now, Chair Janet Yellen and the Federal Reserve board have been faced with a dilemma: how to raise rates when most of the developed world is going in the opposite direction?

The US Economy

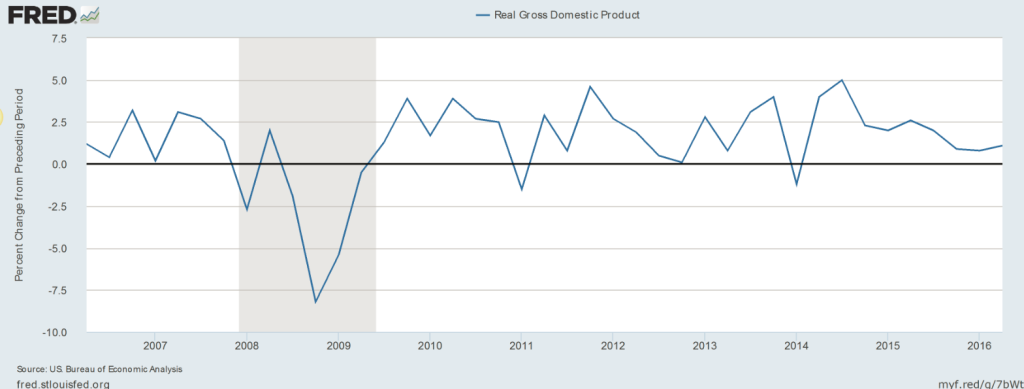

The economic data in the United States has continued to show improvement, but at a slow pace. Let’s take a look at three indicators the Federal Reserve analyzes for monetary policy. The chart below shows US GDP since the recession (shaded area).

While the growth rate snapped back from below -7.5%, the average rate during the recovery has been an anemic +1.2%. This is the slowest GDP growth rate for a recovery since WWII and it implies a weak, stagnant economy susceptible to the smallest changes in monetary policy.

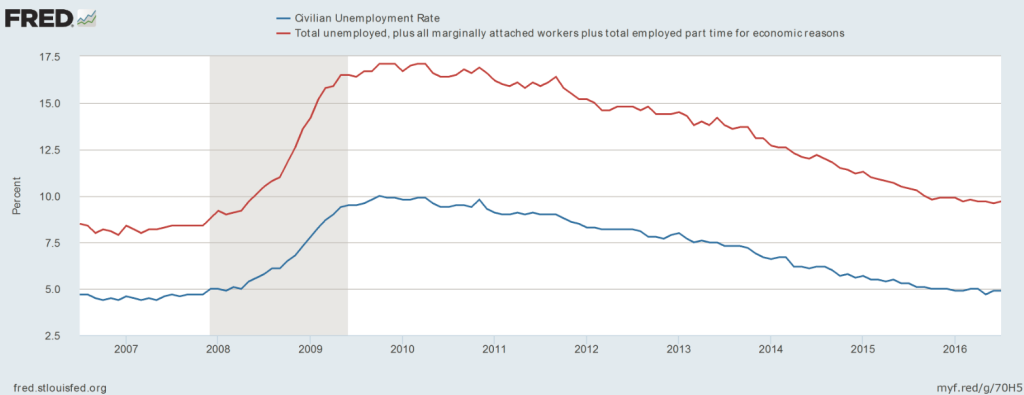

The next chart shows the US civilian unemployment rate (blue, U-3) with the total unemployed rate (red, U-6) over the same period.

Prior to the recession, the spread between the U-3 and U-6 was about 3 percent; this indicates that there were around 3 million people employed part time but looking for full-time work. After the recession, this spread moved out to 5 percent and shows there are 2 million more (total of 5 million) looking for full-time work. Additionally, the labor force participation rate is back down to the levels of the 1980s, meaning the size of the labor pool has shrunk and contributed to the drop in the U-3 rate. This means that the conventional, media-focused US unemployment rate doesn’t reflect all of the underlying softness of the US labor market.

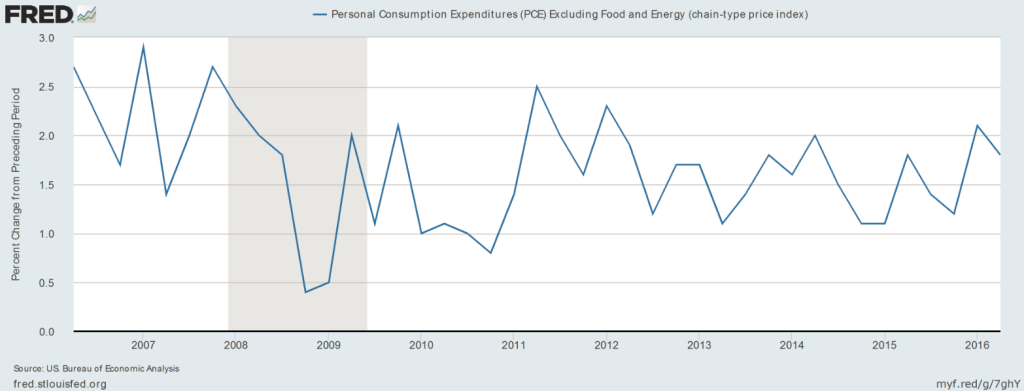

Finally, we turn to what the central bank looks at for inflation. The Fed does look at CPI, but prefers the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), ex-food and energy indicator to provide a clear picture of what prices are doing. The Fed targets a rate of 2.0% as the near-ideal level of inflation.

The chart clearly shows prices remaining consistently below the Fed’s target rate and would indicate the Fed should be in no hurry to raise interest rates.

These GDP, unemployment, and inflation indicators indicate why the Federal Reserve has gone very slowly in tightening monetary policy.

But wait, there’s more!

There are two more considerations for Janet Yellen and the team to consider when raising interest rates. Why? Because the Fed’s decisions don’t occur in a US domestic vacuum.

First, the US dollar. When Ben Bernanke was chairing the Fed in 2014, the central bank indicated it was pleased with economic growth enough to begin to taper down on the quantitative easing program (QE). This caused a surge in US long-term interest rates (10yr US Treasury yield went from 1.5% to 3.0%) and a 25% surge in the US dollar over a 7-month period. The combination further tightened US financial conditions and acted as another rate hike, in that it tamped down inflation and economic expansion somewhat.

During this time, Japan and Europe were headed in the opposite direction economically. Their central banks reacted with the same aggressive adoption of easy monetary policy that the Federal Reserve had used. The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank utilized quantitative easing to drive down both short-term and long-term interest rates. Since short-term rates were already very low, these central banks went further and adopted negative interest rate policies. In recent months, both Japan and Europe have arrived at negative interest rates on their sovereign 10-year debt. In their latest quarterly report, the BIS (Bank for International Settlements) estimated that in the third quarter:

Conservative estimates of the amount of government bonds trading at negative yields surpassed $10 trillion within days after Brexit. Negative yields gradually spread to investment grade corporate bonds in AEs. By late August, some market sources reckoned that up to 30% of the euro area high-grade corporate fixed income market was trading at negative yields. In July, the German treasury was able to publicly place 10-year bonds at negative yields (-0.05%) for the first time ever.

Negative Japanese and European interest rates coupled with a currency that will likely strengthen if US rates are raised have helped to persuade the Federal Reserve to essentially sit on its hands.

On to December!

The three takeaways from today’s meeting are the following. One, the Fed didn’t raise rates today, but will likely raise rates in December. Two, the Fed will not be in any hurry to have additional rate hikes in 2017. Three, the Fed will allow wage and inflation pressures to rise significantly from current levels before acting aggressively to tighten monetary conditions. The danger is that the Fed allows inflation pressures and the stock market to rise too rapidly before stepping in to slow things down.