Executive Summary:

- Over 200 countries attended COP26 to review previous pledges and set a new path forward to limit climate change and global warming.

- The outcome was the Glasgow Climate Pact (GCP) that has the goal of limiting the growth of atmospheric temperatures to less than 2 percent Celsius.

- The US and China made a pact to work together to meet a lower goal of 1.5 percent Celsius.

- The agreements are unenforceable and remain pledges until country legislators write laws to enforce the commitments.

- Due to this, GCP will not be successful in limiting global temperatures rising to either 1.5 or 2.0 Celsius.

After two weeks of negotiations over climate change, the COP26 finally came to an end on November 13 with an agreement to “accelerate” climate action “this decade”, hoping to limit global warming to below the 1.5C goal set in the 2015 Paris Agreement. Negotiations were particularly challenging at this conference as the event had to be extended for an extra day to finalize the decision. Although this is the first agreement ever to set a plan for coal reduction, for many, the decision has fallen short of expectations.

In this article we look at the major outcomes of the COP26 and the role played by the US. We’ve previously produced research on climate change and how countries have been adopting policies in response. In a past article, we’ve also discussed the expectations heading into COP26 and climate change policies set by the Biden administration. The US has played a significant role in the COP26, which makes it worth looking at the conference’s major outcomes and how this can affect US policy moving forward.

What Were the Expectations Ahead of the COP26?

Since 1995, the UN has been bringing together close to 200 countries for global climate summits, called COPs. Different countries gather every year at the COP or “Conference of Parties” to discuss climate change, which has gone from being a fringe issue to a global priority. Most notable maybe is the infamous 2015 Paris agreement born out of the COP21. Following the massive climate crises in many countries during 2020 and 2021, including wildfires, floods, hurricanes, and droughts, the COP26 came with special urgency. In its latest 2021 Assessment Report the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a “code red for humanity” with the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres pressing that “the alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable”. In a statement at the COP26, Guterres further stressed that “our fragile planet is hanging by a thread.” He added that “It is time to go into emergency mode – or our chance of reaching net zero will itself be zero.”

More than 190 countries and thousands of negotiators, government representatives, and businesses looked forward to the COP26 summit, expecting negotiations around multiple topics on climate change. Heading into the conference, we expected discussions on issues related to:

- Updated country pledges and Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to reduce CO2 emissions.

- Carbon market mechanisms (carbon trading and taxes).

- Funding for climate “adaptation” and “loss and damage”.

- Nature-based solutions (NBS).

- Common timeframes for countries’ NDCs.

Earlier this year the US President Joe Biden pledged to cut greenhouse gas emissions by half in 2030, from the 2005 levels. China also announced major commitments to reduce CO2 emissions and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Being the world’s two largest producers of CO2, hearing pledges from the US and China might have raised some optimism heading into COP26. Nevertheless, the credibility of such countries to stand by their agreements are often questioned. This is especially the case as developed countries continue to resist attempts to finance the needed climate action in developing nations. Developed countries are historically the biggest emitters of CO2, which is why many vulnerable nations insist that they finance climate adaptation and loss and damage. At the start of COP26, the Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda stated that if “no formal mechanisms for loss and damage compensation” were to be established, “member countries of the UN may be prepared to seek justice in the appropriate justice bodies.”

The Biden administration is perhaps the largest adopter of climate change policies in US history. As we have discussed in a previous article, the $3.5 trillion social policy and spending bill, Build Back Better (BBB), has substantial allocations to climate change and environmental policy. In the original bill, $198 billion was allocated to the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, in addition to $67 billion to the Committee on Environment and Public Works. Now, the $3.5 trillion social spending bill has been stripped down to around $2.0 trillion and these amounts will be greatly reduced. The House is expected to pass its version of BBB and send it to the Senate for likely further changes.

Not being able to go into COP26 with BBB in place, the credibility of the US as a climate leader was questioned. As Rachel Kyte, dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University and a climate adviser for the United Nations Secretary-General, put it “The whole world is watching. If these bills don’t come to pass, then the US will be coming to Glasgow with some fine words” but “not much else. It won’t be enough.”

Key Outcomes and the Glasgow Climate Pact

After two weeks of heated negotiations over the Paris Agreement “rulebook” and trying to keep the “1.5C alive”, the conference finally concluded with the “Glasgow Climate Pact”. Among others, those are the major highlights of the written agreement:

- A “request” for countries to “revisit and strengthen” their climate pledges next year.

- A call for the “phasedown” of coal and “phaseout” of fossil fuel subsidies.

- An “urge” for developed countries to at least double adaptation climate finance by 2025.

- A two-year” work program” to define a new “goal for adaptation”.

- A two-year “Glasgow Dialogue” to “discuss the arrangements for the funding of activities to avert, minimize and address loss and damage.”

- An invitation to “consider further actions to reduce by 2030” non-CO2 emissions, including methane.

While reaching an agreement is by itself an unprecedented achievement, many parties have been disappointed with the final decision. The decision is the first ever climate deal to explicitly set a plan for reducing coal. Coal burning is responsible for almost 46% of global CO2 emissions and accounts for 72% of electricity greenhouse emissions. For COP 26 attendees, this makes coal the main target for reaching the climate agenda goals. Whether the COP26 was a success or not is debatable. Two issues especially raised criticisms; first, the weakened language over “phasing down” rather than “phasing out” coal, and second, the resistance of developed nations to offer the much-needed climate financing.

At the closing meeting of the COP26, the final agreement had a last-minute change of language from an earlier statement of “accelerating efforts towards the phase-out of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies” to a final agreed version of “accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.” This final weakening in language was proposed by the Indian minister of environment. The shift in language created serious disappointments among many countries who criticized the fact that the final turn in stance has been agreed in private negotiations between the US, EU, China, India, and the UK. Being among the world’s largest CO2 emitters, many have questioned the credibility of their pledges and climate plans. In an emotional speech, the COP26 President, Alok Sharma, expressed his disappointment stating that he was “deeply sorry” for the last-minute shifts in the climate deal. On the other hand, the US and UK saw the outcome as a positive step forward to end the climate crisis. The US envoy for climate, John Kerry, stated that the summit was unexpected to result in a decision that “was somehow going to end the crisis”, but that the “starting pistol” had been fired. The executive director of Greenpeace International, Jennifer Morgan, was also more optimistic stating that: “They changed a word, but they can’t change the signal – that the era of coal is ending.”

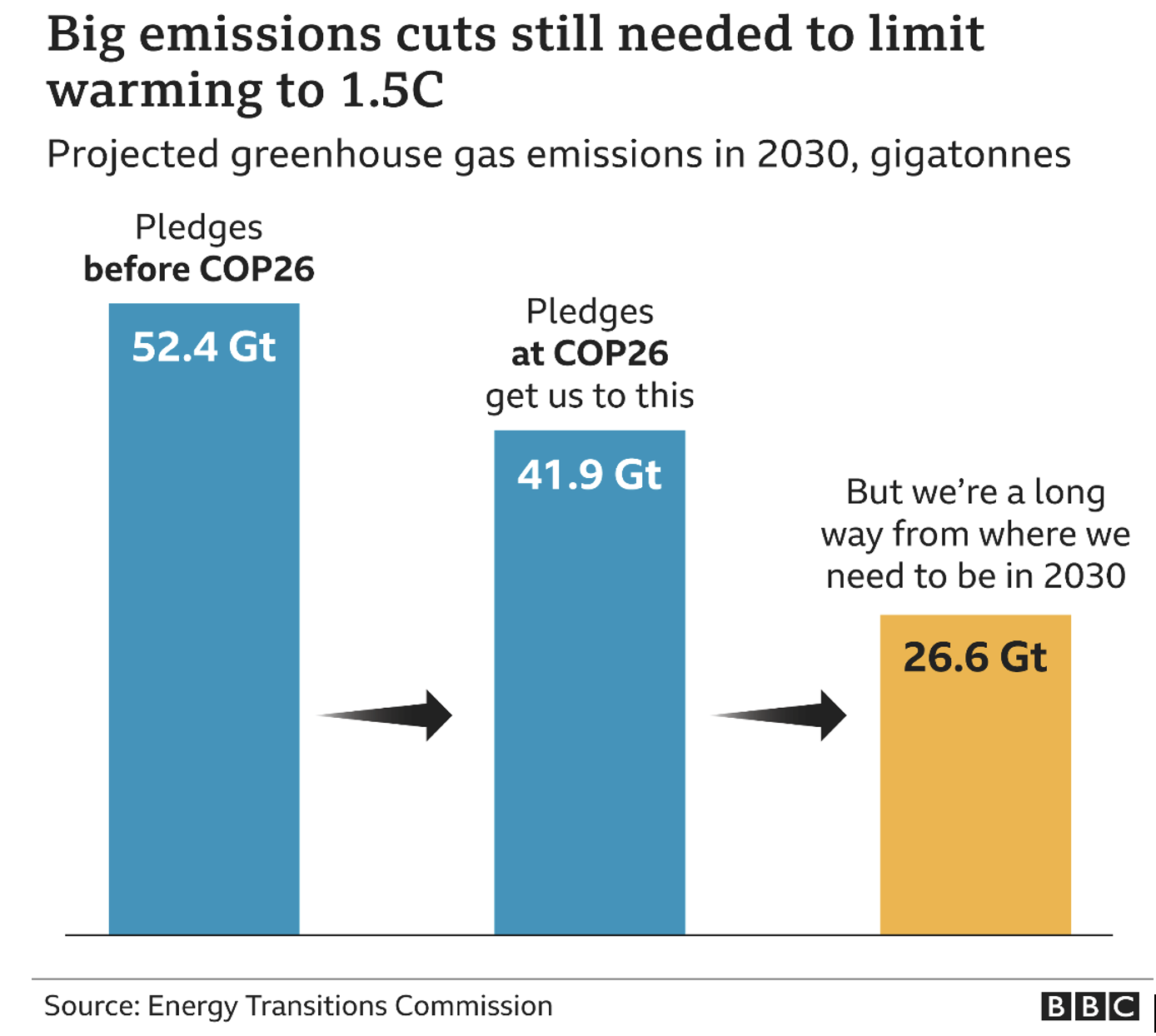

While the first official agreement to reduce coal may be a critical step to the way forward, nevertheless, current pledges remain insufficient to meet the 1.5C goal by 2030. If fulfilled, pledges made at the COP26 can only limit global warming to around 2.4C. The graphic below shows that to reach the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5C, greenhouse emissions will need to be almost halved by 2030. Between current pledges to those needed, a gap of 15.3 Gt remains. Countries are expected to return next year to strengthen their pledges and commitments towards abandoning coal. In another study by the Climate Action Tracker, results showed that Key Cop26 pledges could only push us 9% closer to the 1.5C pathway. Of course, under the assumption that countries keep their promises. It’s likely most will not.

Climate financing was most probably the largest disappointment of the negotiations. At the 2009 COP15, developed countries committed to collectively mobilize $100bn per year by 2020, to finance the “climate action” needs of developing countries. Yet, prior to the start of COP26 developed countries acknowledged their failure to meet the $100bn goal. In the COP26 decision text it was noted with “deep regret” that the $100bn goal has not “yet” been met. Criticism was heightened when John Kerry, the US envoy, stated that developed countries only shortly missed their target as they were able to mobilize between $95-98 billion according to the OECD. But according to the official OECD statistics, developed countries are expected to mobilize between $92-97 by 2022. By the end of 2021, the expectation is around $83-88 billion. The “Climate Vulnerable Forum” representative, which includes several vulnerable parties in the summit, expressed his discontent saying: “I believe that the money is there – they don’t want to release it. Because looking at Covid… billions of dollars have been used over the years to take care of Covid. Do you think Covid is more important than climate change?”

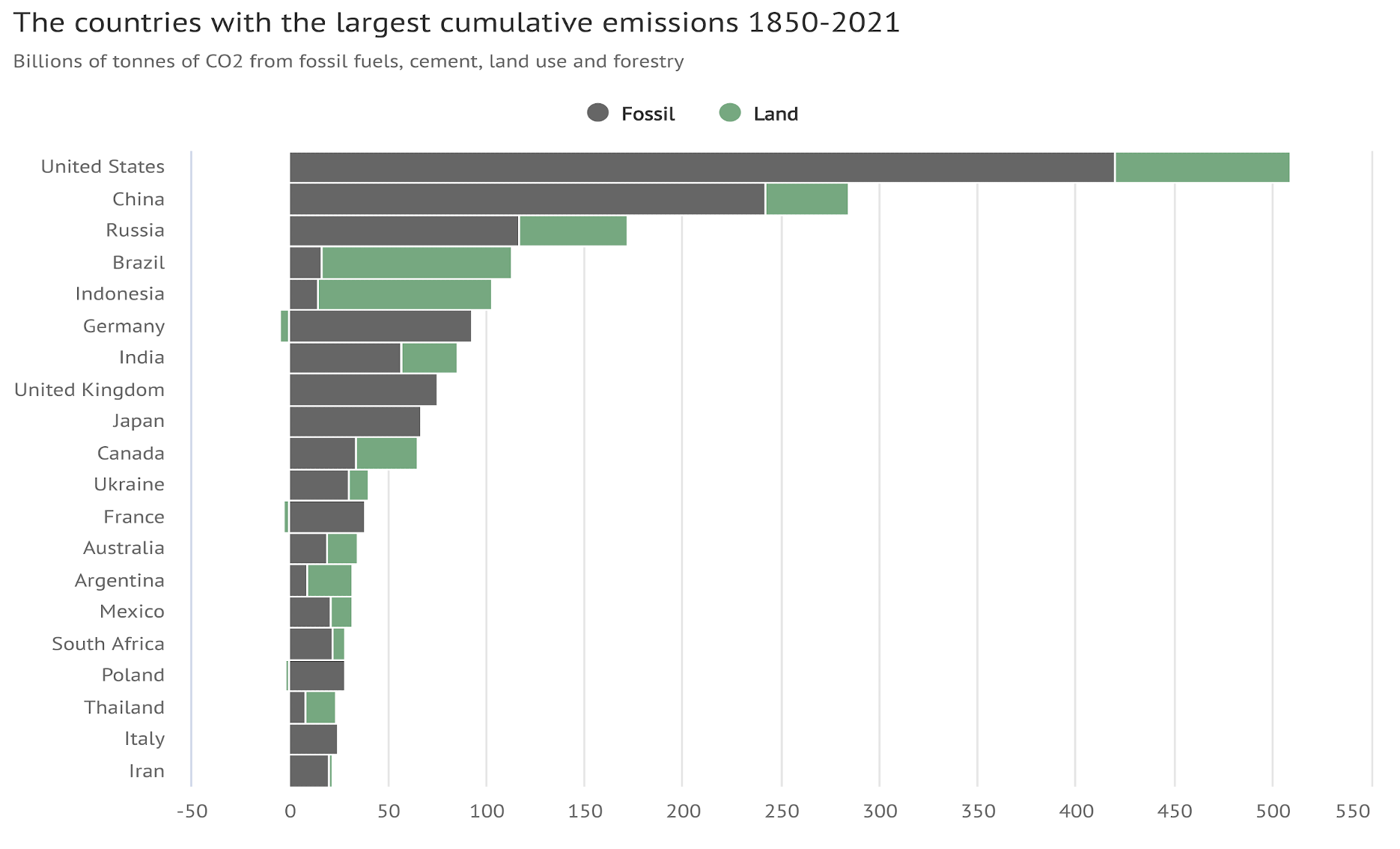

Throughout the event there has been a clear resistance from richer countries to have a multilaterally agreed definition of “climate finance”. Vulnerable and wealthier nations entered the COP26 with opposing priorities. On one hand, vulnerable countries argue that industrial countries are mostly responsible for the historical and current climate problem, and hence should assist developing countries in adaptation and dealing with loss and damage. On the other hand, developed nations fear that if they give in to the negotiations, they might be forced to pay due compensations for their historical responsibility. In an analysis of CO2 emissions since 1850, Carbon Brief showed that the US is the country with highest cumulative emissions over the timeseries. By the end of this year, the US would have emitted a total of 509 GtCO2 since 1850, accounting for 20.3% of the global total and associated with around 0.2C of global warming.

The 20 largest contributors to cumulative CO2 emissions 1850-2021, billions of tonnes. Source: Carbon Brief

In its final text, the agreement “urged” developed countries to meet the financing targets “urgently and through to 2025”, without any reference to covering prior shortfalls. A call was also made for developed countries to “at least double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation” by 2025 from 2019 levels. Several developed countries, including the US and EU, have also committed to the Adaptation Fund. The fund provides a total of $850 million to support climate adaptation in vulnerable countries, of which $326 million were raised in new pledges in COP26. The fund has the advantage of being 100% grant-based rather than indebting poorer countries. To that cause, the U.S. newly pledged $50 million. In addition to adaptation financing, the issue of compensating “loss and damage” was raised and was especially opposed by the US. The final decision was to create a two-year “Glasgow Dialogue” to discuss future arrangements on that matter. Concerns have also been raised about the post-2025 climate financing. Whether for adaptation or Loss and Damage, provided amounts are only a fraction of what’s needed. A recent study by the UN Standing Committee on Finance claimed that vulnerable nations would require nearly $6 trillion up to 2030, including domestic funds, to support just 40% of their NDCs.

The US-China Climate Statement

The biggest surprise to the COP26 observers was probably the “US-China Joint Glasgow declaration on Enhancing Climate Action in the 2020s”. Being the two largest CO2 emitters in the world, coming to a joint agreement despite their historical rocky relationship was seen as an optimistic step towards resolving the climate crisis. Together, the US and China account for more than 40% of global CO2 emissions. The document was announced by the US and Chinese climate envoys on November 10, stating that the agreement was the result of no less than 30 meetings between both parties since the start of the year. Kerry stated that the declaration was born as the two nations’ leaders hoped that despite “areas of real difference,” both countries “could cooperate on the climate crisis”.

According to the statement, both countries have committed to work together to reach the 1.5C goal. A working group will be established and regularly meet to “address the climate crisis and advance the multilateral process, focusing on enhancing concrete actions in this decade.” In the statement, intentions of phasing down coal, reducing CO2 and methane emissions, as well as fighting deforestation have been made.

Experts are optimistic that this agreement will set the ground for more future cooperation between countries to end the climate crisis. In their statement both countries have stated that they “recognize the importance of the commitment made by developed countries to the goal of mobilizing jointly $100b per year by 2020 and annually through 2025 to address the needs of developing countries”. Genevieve Maricle, director of US climate policy action at the World Wildlife Fund, expressed her optimism over this deal stating that “Between them they have the power to unlock vast financial flows from the public and private sectors that can speed the transition to a low carbon economy.”

The Global Methane Pledge

An announcement was made last September on the EU-US “Global Methane Pledge”, to reduce global methane emissions by 30% in 2030. A key announcement at the COP26 was the formal launch of the pledge. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that accounts for around half of the 1.0 degrees Celsius net rise in global average temperature since the pre-industrial era, according to the IPCC. The pledge was described by Biden as a “game-changing commitment”. A Total of 109 countries have signed the agreement, accounting for over 50% of global methane emissions. Countries such as Australia, China, India, and Russia have not yet joined, although China has expressed intention to discuss issues on methane with the US next year. In support of mitigation, the US and EU also announced technical and financial assistance of $328m from 20 philanthropic organizations, to support the implementation of the pledge.

Conclusion

With the end of the long-awaited event, the question then is whether countries will stand by their commitments or not. Even though the first ever agreement to phasedown coal was born out of the COP26, the outcomes are by far a disappointment to many parties and environmentalists. Most of the decisions were meek with no real obligations in place. If anything, most of the decisions on pledges and climate financing have been carried forward to the next year or two, urging or requesting countries to raise their bars. While the climate crisis is a collective burden, different countries still hold opposing priorities and agendas.

Perhaps the US-China joint declaration marked an optimistic step in the journey to ending the crisis. Experts are hoping that this will not only put the largest emitters on the right path, but that it will also signal to other countries the urgency to join the pact. Nevertheless, without passing the Build Back Better infrastructure bill, the US leadership role was reduced. Also, there were poor optics on the US holding a historic oil and gas lease sale on November 17, opening over 80 million acres in the Gulf of Mexico to auction for oil and gas drilling. The sale came merely four days following the close of the COP26, where the US pledged to cut emissions and marked a reversal in a previous commitment to shut down new oil and natural gas leases.

It underscores the difference between the Biden administration’s attempted climate policy and the current US law. And shows the need for Congress to act if permanent change is to occur. Otherwise, the next Republican administration will likely unwind the executive orders and some of the regulatory changes made. COP 26 is a stark reminder that pledges, and commitments alone are not enough to limit climate change.