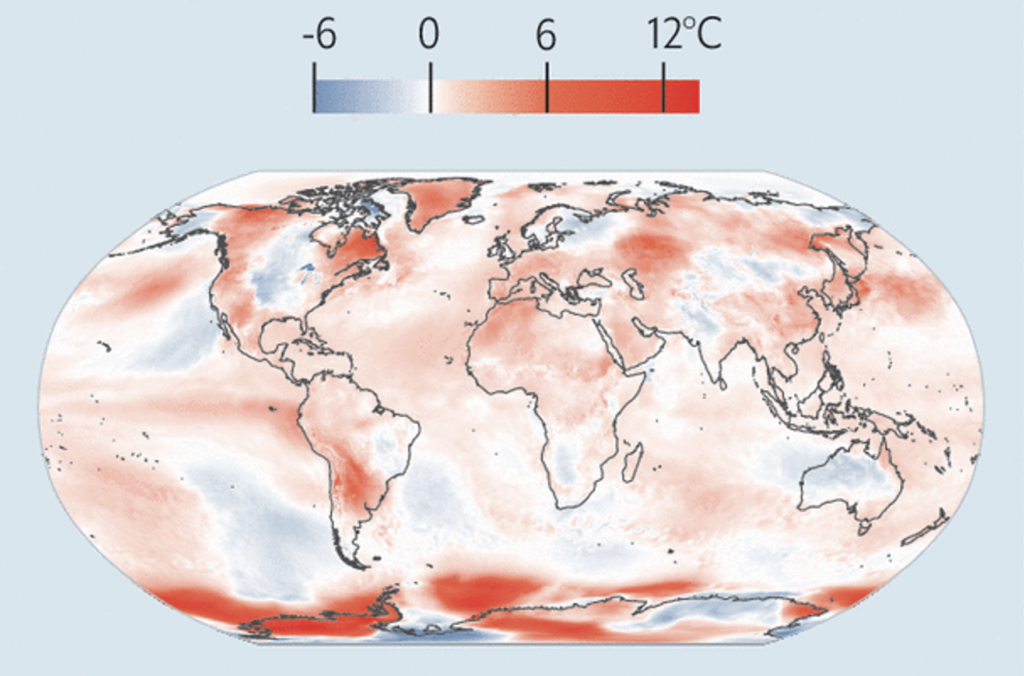

El Niño is impacting the world economy and worsening an already difficult climate environment. With extreme heat waves sweeping across the globe, scientists are grappling with the potential of 2023 becoming the hottest year on record. A global temperature of 17.2°C (approximately 63°F) in July shattered all previous records, sending shockwaves through climate research circles. As vividly depicted in Figure 1 below, temperature anomalies for July surged, revealing stark deviations from the 1981-2010 average.

Figure 1 – Average Air Temperature for July 1st-12th 2023, Deviation from 1981-2010

Source: The Economist, based on Copernicus, ERA5.

Beyond the evident impact of mounting greenhouse gas emissions, there’s another key player in the warming game – El Niño. This climatic phenomenon, known as the “little boy” in Spanish, periodically emerges every 2-7 years, elevating sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific and subsequently unleashing searing heat waves across various corners of the world.

Despite being a phenomenon of natural climate variations, the intensity and frequency of El Niño have been amplified by increased temperatures from higher greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, scientists suspect. While there is yet no consensus on whether this argument holds or not, evidence suggests that the events are getting stronger in recent decades.

Josef Ludescher, a scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, points to a critical relationship between temperature rise and El Niño’s impact. According to him, as temperatures soar, the atmosphere’s capacity to hold moisture expands, with each 1°C rise enabling the air to accommodate 7% more water vapor. This heightened moisture capacity has profound implications, potentially intensifying rainfall during El Niño events under warmer conditions.

We have covered in previous articles how the world has been failing to limit climate change and how this has contributed to devastating climate events, threatening lives and distorting food and production systems. Against the backdrop of a planet grappling with climate crises, the failure to curtail climate change is no longer a distant reality. Devastating climate events are wreaking havoc on lives and disrupting critical food and production systems, emphasizing the urgent need for concerted global action towards mitigation and adaptation.

In this comprehensive article, we traverse the intricate landscapes of El Niño’s past, present, and future, in addition to its potential impacts on the global economic system. Through meticulous examination, we aim to unravel the intricate web of influences that drive it, equipping you with a deeper understanding of the phenomenon, El Niño.

El Niño Defined & World Impact

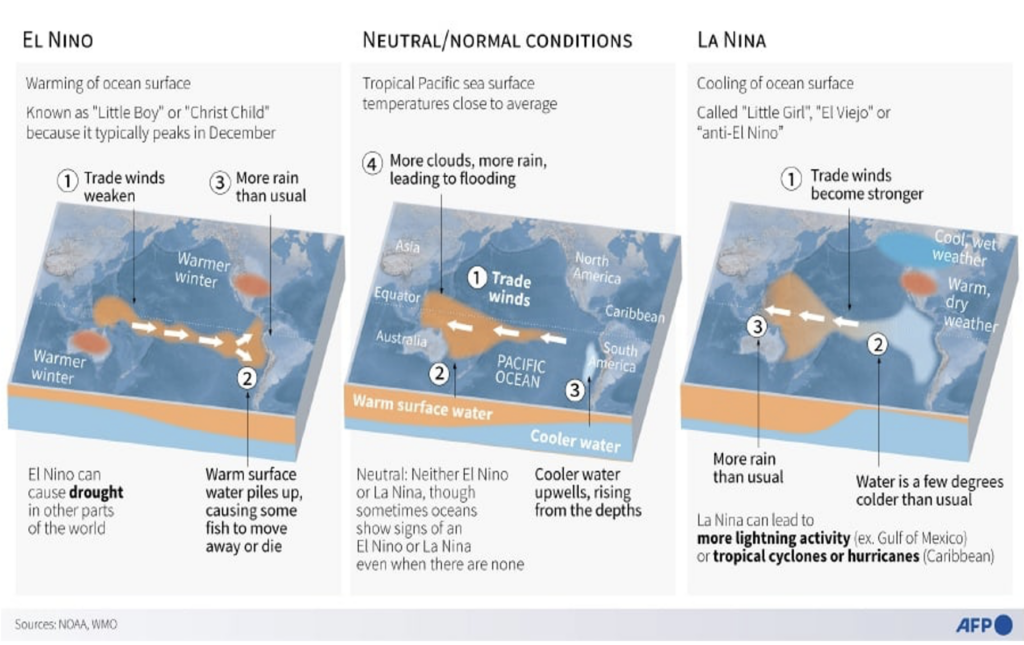

At its core, El Niño is a natural climatic phenomenon that occurs irregularly every two to seven years. It is characterized by the warming of the ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific Oceans, which in turn has far-reaching effects on global weather patterns. El Niño leads to shifts in the distribution of warm and cold ocean waters, ultimately influencing atmospheric circulation, rainfall, and temperature patterns worldwide.

It is the warm phase of a natural climate phenomenon known as El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), commonly referred to as the El Niño-La Niña climate pattern. With its ability to alter the global atmospheric circulation, impacting temperature and precipitation all over the world, ENSO is one of the most significant climate phenomena. ENSO can exist in one of three phases; a “Neutral” phase, where the tropical Pacific Ocean’s surface temperatures remain close to average, in addition to the two opposite extremes, “El Niño” and “La Niña” phases. The graphic below demonstrates what happens during three different ENSO phases along the tropical Pacific.

Figure 2 – El Niño and La Niña Climate Patterns

Source: New Straits Times.

El Niño, the warming phase, is typically declared when sea surface temperatures in the tropical central-eastern Pacific Ocean rise by at least 0.5C above the long-term average, for five consecutive three-month periods. Under normal conditions, sea surface temperatures in the Pacific tend to be cooler in the east than the west, as “easterly” or “trade” winds, those that blow from the east to the west along the equator, warm the water. However, during an EL Niño event, such trade winds either weaken or reverse direction (become “westerly” winds), warming the water in the east instead. Rainfall tends to decline over Indonesia (the western Pacific) and increase in the tropical central-eastern part of the ocean. Throughout history, El Niño events have been associated with extreme weather conditions across the globe. These events can bring about droughts, floods, hurricanes, and other disruptions to ecosystems and societies. Notable historical instances include the 1982-1983 and 1997-1998 El Niño events, which left lasting impacts on various regions.

La Niña or the cooling phase, on the other hand, is typically declared when sea surface temperatures in the central-eastern Pacific Ocean drop by at least 0.5C below the long-term average. Easterly winds become stronger than normal, pushing warmer waters even further to the west, while rainfall increases over Indonesia and declines in the tropical Pacific.

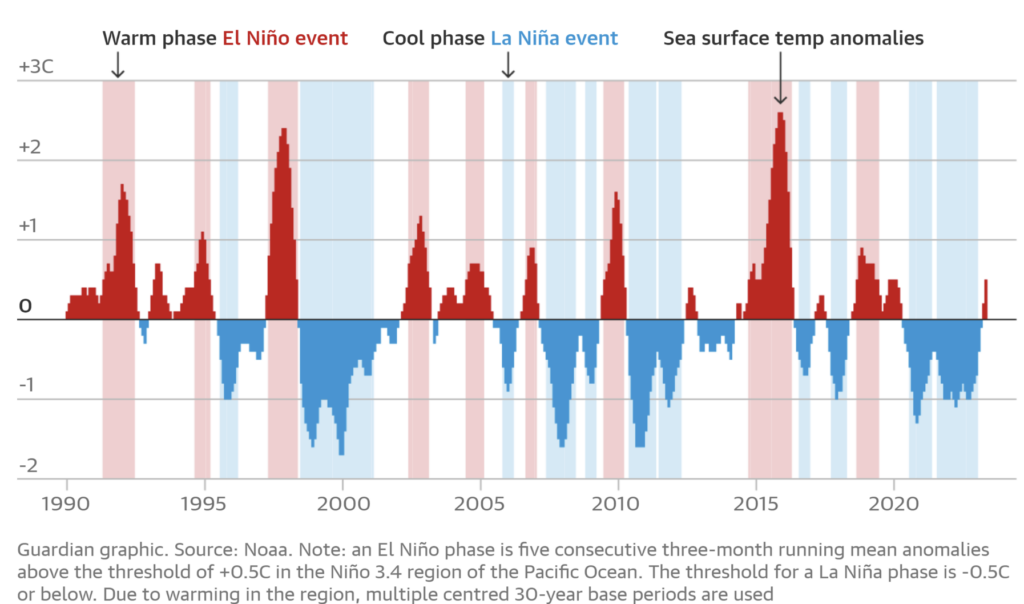

As stated earlier, El Niño and La Niña episodes tend to happen every 2-7 years, typically lasting for 9 months to a couple of years. Moreover, La Niña tends to follow El Niño after 1-2 years, with the latter occurring more frequently.

The graph below summarizes the occurrences of El Niño and La Niña events over the last three decades. While an El Niño event occurred during 2018-19, the last major episode was during 2014-16, when 2016 marked the hottest year in history. According to some researchers, this year’s El Niño might break the 2016 hottest year record, with the peak probably hitting in 2024.

Figure 3 – Surface Temperature Anomalies and El Niño/La Niña events in the Pacific

Source: The Guardian.

2023: El Nino Event Declared, Warning of Strongest on Record

In June 2023, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) declared that the world has entered into an El Niño event, stating that “El Niño conditions have developed, as the atmospheric response to the warmer-than-average tropical Pacific sea surface kicked in over the past month.”

Shortly after, another declaration was announced by the World Meteorological Association (WMO) in July, stating that “El Niño conditions have developed in the tropical Pacific for the first time in seven years, setting the stage for a likely surge in global temperatures and disruptive weather and climate patterns.”

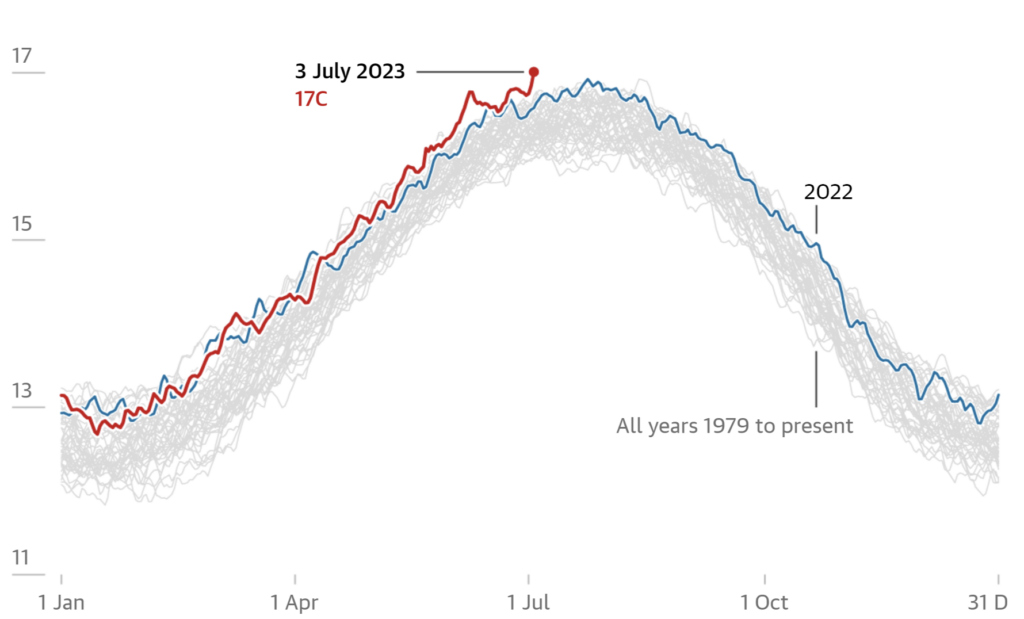

There is a 90% probability that this year’s El Niño will continue into the winter and is expected to be at least a moderate event (probability of 85%), if not a strong one (probability of 56%). According to the WMO, this phenomenon will largely increase the likelihood of witnessing record rises in temperatures and extreme heat waves across the globe. Indeed, as shown in the figure below, global temperatures have reached record-high levels this July. The WMO predicts that, with a 98% probability, one of the next five years and the next five-year period, will mark the warmest period in history, surpassing the 2016 record when EL Niño was especially strong.

Figure 4 – Daily Average Two-Meter Global Temperatures, Above Land and Sea

Source: The Guardian.

The impacts of El Niño largely vary across the world, including heavy or low rainfalls, floods, droughts, storms, cyclones, and wildfires. For example, countries in South America, Central Asia, and the Horn of Africa, as well as the southern parts of the U.S. tend to suffer from excessive rainfall and floods. On the other hand, Australia, Indonesia, and some countries in Central America, northern South America, and South Asia tend to struggle with extreme heat waves, droughts, and wildfires.

Countries in the Pacific region and those around the equator, including those in Central and South America, the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, and eastern and southern Africa, are the most impacted by El Niño. For starters, El Niño is expected to intensify the risk of tropical cyclones in the Pacific region. Moreover, this year’s El Niño is expected to heighten the risk of already occurring wildfires in Indonesia and Australia, as it results in hotter and drier weather conditions. On the other hand, in East Africa, impacts will be seen through increased risks of heavy rainfall and flooding.

Although El Niño is a tropical Pacific phenomenon, its effects are not restricted to such regions. According to Regina Rodrigues, an oceanographer at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Brazil, “El Nino is responsible for a lot of extremes… Every country, in one way or another, is affected.” For instance, exceptionally colder winters and hotter summers can be expected in the northern parts of the U.S., whereas more rainfall will probably be experienced in the south of the country. Similarly, in Europe, northern parts of the continent might experience colder temperatures in the winter and hotter summers, while wetter weather conditions in the south. Other regions of the world will likely not be spared either. For example, a study that looked at data and simulations of summer rainfall over the Arabian Peninsula between 1981 and 2015 concluded that El Niño was linked to over 70% of drought years in the region, while La Niña affected almost 40% of its flood years

Size of Global Economic Impact

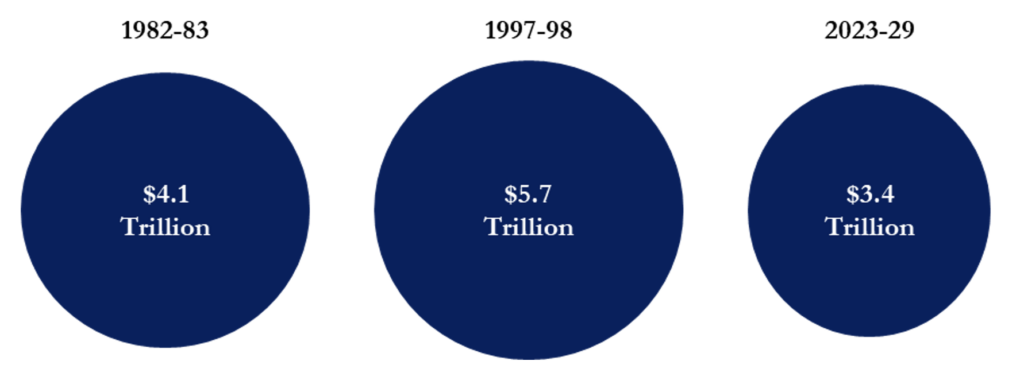

In a recent study, researchers at Dartmouth College estimated that even if current climate pledges are fulfilled, an El Niño event starting in 2023 could potentially cost the global economy up to $3.4 trillion by 2029. The world’s poorest nations are expected to bear the brunt, accounting for most of the economic impact. According to Callahan, a lead author, “In the tropics and places that experience the effects of El Niño, you get a persistent signature during which growth is delayed for at least five years.” The estimates further show that a strong event, similar in magnitude to the past two El Niño incidences, could cost the U.S. economy alone as much as $699 billion.

As shown in the figure below, past El Niño events have also been responsible for devastating economic losses, estimated at around $4.1 trillion and $5.7 trillion during the 1982-83 and 1997-98 episodes. Extreme weather incidents associated with the EL Niño event are expected to weigh on global economic activity, including distorting food and ecosystems, pushing up prices, stalling industrial production, destroying infrastructure, and impacting human capital.

Figure 5 – Historical Global Economic Losses of El Niño Events

Source: Author’s Diagram, based on Callahan and Mankin (2023).

The Impact on Food Systems

The global food system is intricately linked to climate patterns, making it particularly susceptible to the disruptive influence of events like El Niño. The warming of ocean waters associated with El Niño can set off a chain reaction of climatic changes, which in turn significantly affect agricultural production and food security around the world.

According to Elyssa Ludher, from the Climate Change in Southeast Asia program at the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, “The full impact on agriculture yield is dependent on the severity of the El Niño event…But the challenge is that it is coming on top of other climate and geopolitical events causing production losses and supply disruptions … so all in all, it’s a concerning situation.”

The World Food Program (WFP) estimates that during the 2016 El Niño event, more than 60 million people needed humanitarian assistance due to food insecurity. This year might be even worse, as the number of people facing food insecurity has already reached a record high in 2022. Extreme weather conditions and associated economic effects are expected to escalate the issue, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). With the Ukraine war and the lapsing of the Black Sea Grain Inititative, the impact from this El Nino event could be larger than anticipated.

One of the most immediate and tangible impacts of El Niño on food systems is the alteration of rainfall patterns. Regions that typically rely on consistent precipitation for agricultural productivity can face prolonged droughts during El Niño events. This lack of water availability can lead to crop failures, reduced yields, and even the loss of entire harvests. The poorest countries, whose economies heavily rely on agriculture, for instance, countries in Africa, Asia, and South America, which are already vulnerable due to their heavy reliance on rain-fed agriculture, are particularly susceptible to these disruptions.

According to the FAO, drier conditions associated with EL Niño will particularly affect cropping seasons in areas of Southern Africa, Central America, the Caribbean, and parts of Asia, which already suffer from food insecurity. Moreover, dry conditions will hit global cereal production and exports, including in countries such as Australia, Brazil, and South Africa.

Excessive rainfall in other regions can also negatively impact yields. For example, heavy rainfall could influence cereal exporters in Asia, the U.S., Argentina, and Turkey. Asia, which suffers from extreme heat and lower rainfall during El Niño events, is responsible for around 90% of the world’s rice supply. This July, heavy rains sabotaged rice fields in India, which supplies almost 40% of the world’s grain, leading to the government banning rice exports to ensure adequate domestic supply and stabilize prices, and causing global panic.

El Niño’s effects go beyond just altering precipitation patterns. Changes in temperature and humidity can lead to shifts in the distribution and behavior of pests and diseases. Warmer conditions can create favorable environments for certain pests to thrive, leading to increased infestations that damage crops. Furthermore, the spread of diseases affecting crops and livestock can intensify during El Niño events, exacerbating the challenges faced by agricultural communities.

Also, El Niño events tend to distort marine ecosystems as they affect the migration of fish and reduce catches, which can lead to devastating losses in the fish industry and affect the global food system.

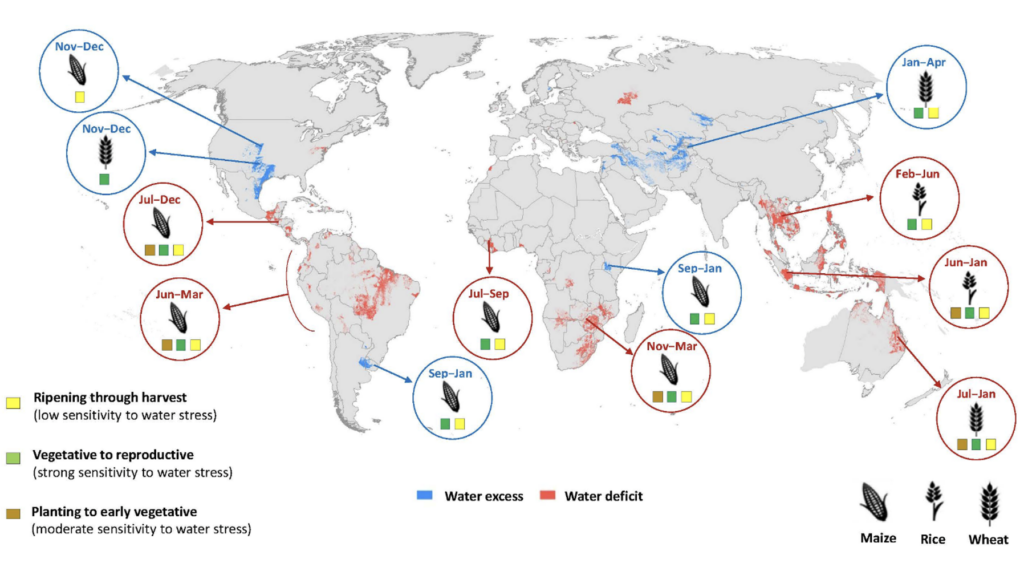

The figure below demonstrates the agricultural regions with a high correlation between El Niño events and dry/wet conditions around the world; those with high likelihood to be impacted.

Figure 6 – Agricultural Areas with High Correlation Between Dry/Wet Conditions and El Niño Events

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Impact on Industry & Tourism

El Niño’s far-reaching effects extend beyond the realms of agriculture and climate, deeply impacting industries and the tourism sector. As weather patterns shift dramatically during these climatic events, industries that rely on stable conditions are faced with challenges that can disrupt operations, lead to economic losses, and affect local economies. Similarly, the tourism sector, which thrives on predictable and appealing weather, faces fluctuations that can sway visitor numbers, revenue, and infrastructure sustainability.

Severe weather conditions such as cyclones, hurricanes, or floods could ruin infrastructure, bring production to a halt, and distort supply chains. In a previous article, for example, we’ve discussed how climate change and extreme weather events can impact major industries, such as plastics, across the globe. Other examples include heavy rainfall in Latin America, which disrupted Chile’s copper mining industries, the country’s primary export.

Extreme heat waves tend to dry up rivers and threaten supply chains. In Germany, for example, the Rhine River is down to below 100 centimeters at the town of Kalb, making it almost impossible for barges that carry industrial goods and coal to pass through. Moreover, in Eastern Europe, the Danube River fell to 135 centimeters at Budapest, risking a major Ukrainian grain transport route.

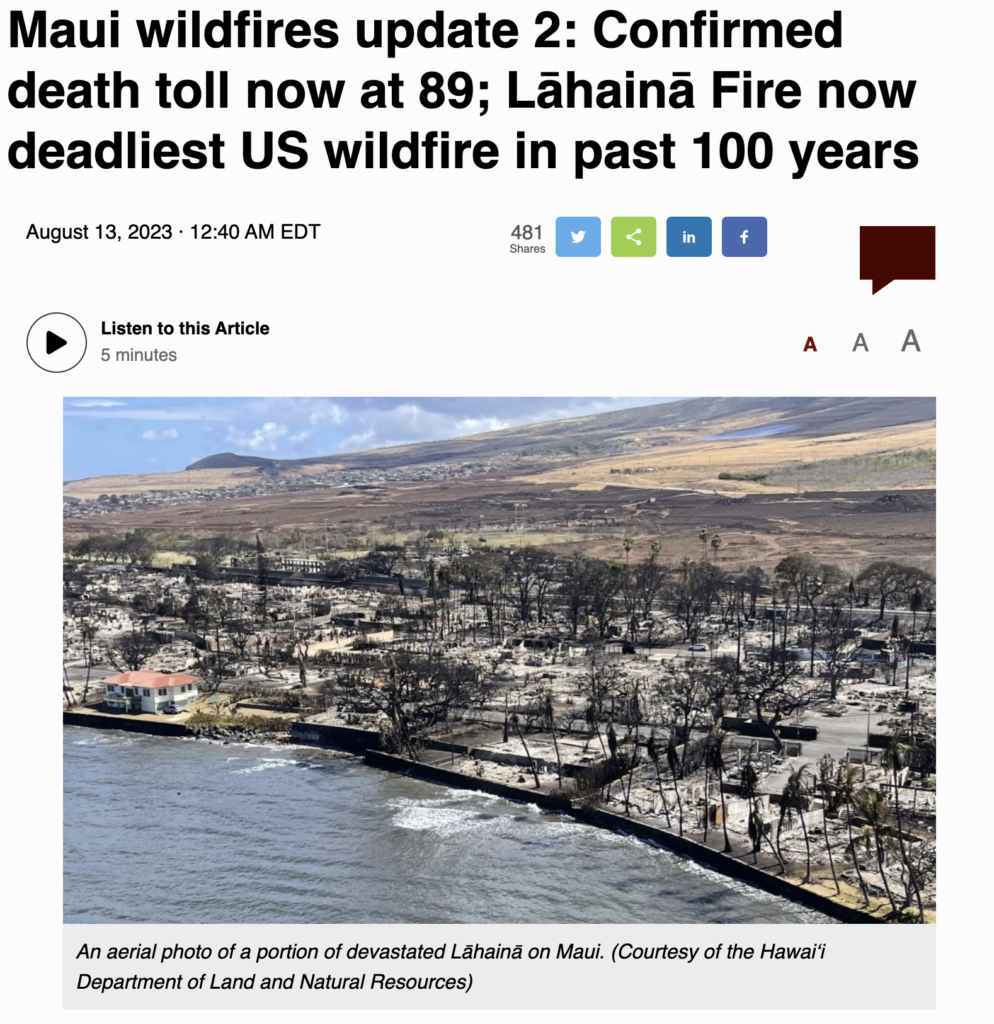

The tourism sector, reliant on pleasant weather and safe conditions, is particularly sensitive to El Niño’s disruptions. Evidence shows that willingness to travel during EL Niño events significantly drops, as demonstrated by a study that looked at 48 natural attraction spots in the U.S. Coastal destinations that attract visitors for beach activities and water sports can be hit by unpredictable weather, deterring tourists and causing revenue losses for local businesses. Similarly, regions known for their natural landscapes and outdoor activities can experience reduced tourist inflows due to unfavorable weather conditions. The Maui fire is an example of what can happen when conditions are ripe for a combined weather and forest fire event, devastating a vacation meca.

Yet, I would caution conflating Maui, Rhodes or Camp fires to simply climate. As the brilliant Dr. Roger Pielke Jr. pointed out:

- Maui County was not experiencing unusual drought conditions last week, as you can see in the figure above. The U.S. Drought Monitorhas drought intensity data for Maui County from January 2000, that’s 1232 weeks 690 of those weeks (or 56%) had greater drought conditions (D0-D4) than the week of 8 Aug 2023. There have been no D3-D4 drought conditions in Maui County since 3 Jan 2023,

- Hawaii has seen multi-decadal climate variability and changes, including a drier period in recent decades (during Nov-Apr), however these changes have not been attributed to climate change by those researchers who have explicitly researched the topic. A 2022 paper concludes, “for all the model precipitation change signals described above, their magnitudes are considerably less than their simulated internal variability of climate on centennial time scales.”

The take-way: be cautious about connecting climate and El Nino to Maui…but be aware we don’t know yet what we don’t know about the fire, the nearby storm and changes to climate.

Impact on Electricity Supply & Demand

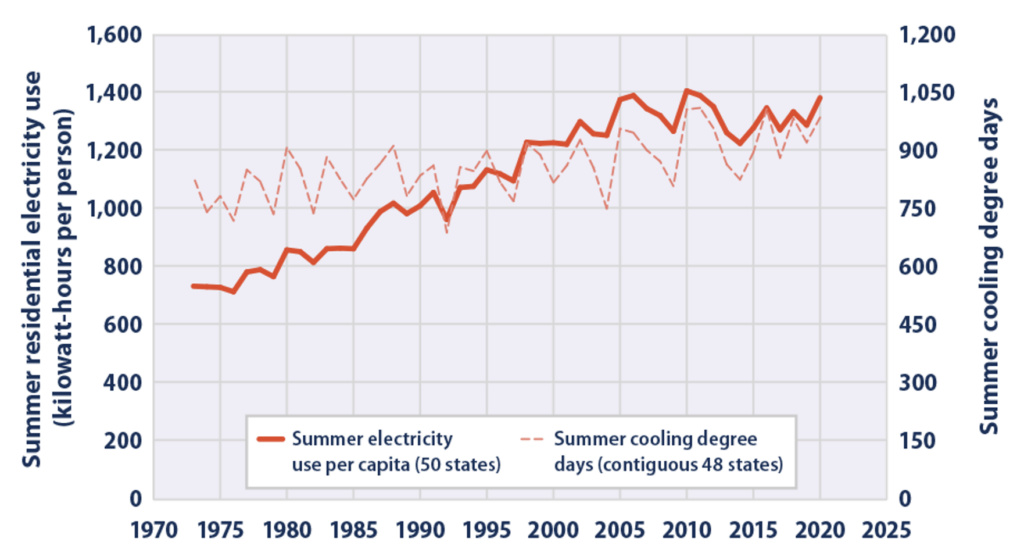

The interplay between climate patterns and energy demand and supply is a complex relationship that can be significantly disrupted during El Niño events. From altering temperature patterns to affecting water availability, the implications for electricity demand and supply are both immediate and far-reaching. Extreme heat waves have already started affecting electricity demand and supply around the globe. As temperatures continued to rise, hitting a record high in July, demand for electricity spiked amid increased cooling/air conditioning needs. Heat waves tend to push up the demand for electricity, especially in summer, putting the electricity system under stress. The figure below shows that the amount of electricity used by the average American at home during the summer months (June, July, and August) has almost doubled between 1973 and 2020.

Figure 7 – U.S. Residential Summer Electricity Use per Capita, 1973-2020

Source: United States Environmental Protection Agency.

As well, extreme weather events such as heat waves, cyclones, and floods can disrupt electricity supply. In the U.S. Gulf Coast, for example, storms may cause a supply-side shock as they damage the oil and gas infrastructure. Moreover, during extreme heat waves, some generators may not produce at full capacity, which can increase the risk of electrical outages, especially as demand peaks. When the grid is under stress, power suppliers tend to deliberately switch off electric supply to some customers to protect the stability of the whole system, also known as load shedding. In Australia, the Energy Market Operator already warned of the risk of outages, as electricity demand may exceed supply due to extreme weather conditions and generator shortages over the next decade.

Even in extreme dryer conditions, energy supply can be threatened in countries that rely on hydropower sources. For example, in China, as rainfall declined by almost 40%, hydropower output fell by 12% since the beginning of 2023. This is a problem that might also affect the U.S., as the Northern parts of the country become drier during El Niño, disrupting the constant flow of water. Moreover, other renewable energy sources, such as wind turbines, tend to be impacted as surface wind speeds tend to drop during El Niño events.

Impact on Inflation

As El Niño impacts food, energy, and other industrial sectors, it is only natural for commodity prices to rally; an issue that is particularly critical given the already high global inflation. One of the primary channels through which El Niño influences inflation is by disrupting agricultural production. As mentioned earlier, El Niño can lead to altered precipitation patterns, resulting in droughts or excessive rainfall in various regions. These weather anomalies can lead to reduced crop yields, diminished harvests, and even complete crop failures. When agricultural output declines, the supply of food and other agricultural commodities contracts, leading to higher prices in the market.

It is estimated that past El Niño events have increased non-energy and energy commodity prices by 4.0 and 3.5 percentage points, respectively. This year, increasing concerns around a new strong El Niño event are already pushing up food commodity prices, including sugar, coffee, and cocoa. On predictions of possible commodity shortages, futures in such commodities are already trading at multi-year highs. Increasing energy demand and distortions in supply will also likely push up energy prices. Moreover, storms, drying rivers, and damaged infrastructure may increase transportation costs, feeding into higher prices for all other commodities. Only as major commodity prices were starting to ease following the recent hikes, a strong El Niño event might push the world into another inflation spiral.

Impact on Human Capital

Human capital can be largely impacted by El Niño events, as it impacts human health and hence productivity. El Niño’s influence on weather patterns can have direct and indirect impacts on public health. Shifts in temperature and humidity can create favorable conditions for the spread of vector-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever. Prolonged droughts can lead to water scarcity, compromising sanitation and increasing the risk of waterborne diseases. Moreover, extreme weather events such as floods and storms can result in injuries, displacement, and mental health challenges for affected communities.

According to the Director General of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, “The WHO is preparing for the very high probability that 2023 and 2024 will be marked by an El Niño event, which could increase transmission of dengue and other so-called arboviruses, such as Zika and chikungunya.” Extreme weather conditions are expected to fuel the breeding of mosquitoes and increase the spread of viral diseases. Dengue, which has been rapidly increasing in the Americas, is especially of concern. In Peru, for instance, recent sharp surges in dengue across almost all regions have pushed the country into a state of health emergency, leading to the resignation of its Health Minister.

The disruptions caused by El Niño events can also extend to education systems. Schools in affected regions may need to close due to adverse weather conditions, compromising students’ learning outcomes. Moreover, the economic strain on families, especially those dependent on agriculture, can lead to reduced access to education as children are often pulled out of school to help with household tasks or to supplement the family income.

What’s Next?

Evidence suggests that the world is expected to see significant changes in ENSO patterns over the next decades, with such changes likely being amplified by more extreme climate change and global warming.

According to a recent study by scientists from the University of Colorado and the University of Washington, despite uncertainties, model simulations predict that EL Niño and La Niño events will likely gain strength in the future, before potentially weakening by the end of the century. In other words, impacts are expected to be more severe with increased rainfall in some parts of the world, while even less rainfall in others. Moreover, the research predicts that El Niño and La Niña events will be concentrated in the Southern Hemisphere summer months (December, January, and February), rather than the rest of the year, with El Niño events followed by longer and stronger La Niña events.

Other scientists from the Pohang University of Science and Technology in South Korea predict that while El Niño events are likely to occur more frequently in the central Pacific compared to the eastern Pacific region, the events will increase in amplitude in the latter, implying a higher probability of extreme occurrences in the east side.

How Bad Could It Get?

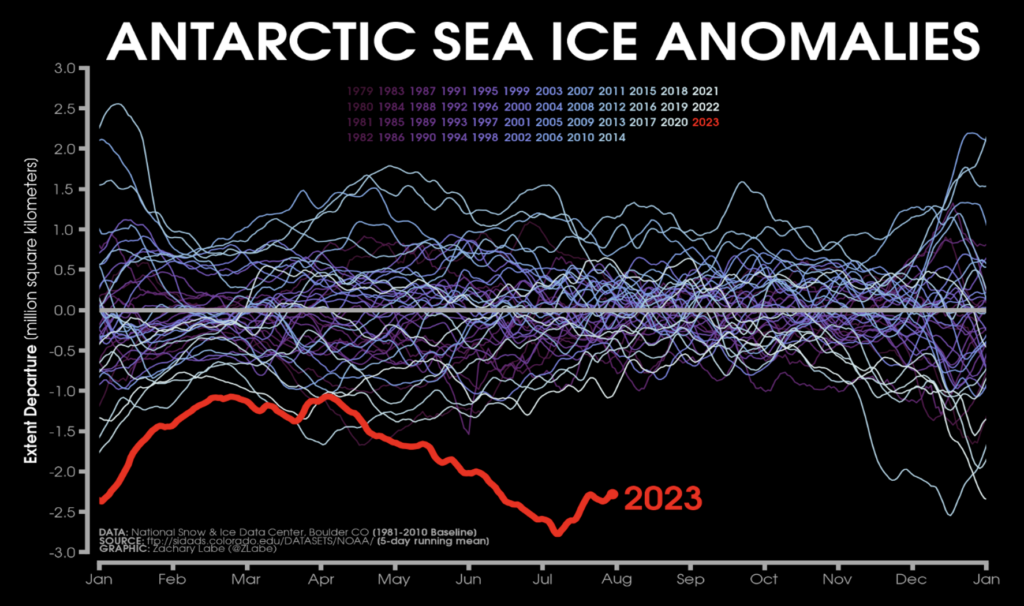

According to the WMO, there is a 66% probability that the average annual near-surface global temperature will break through the 1.5C above pre-industrial levels limit, for at least one year by 2027. This is the global warming threshold that leaders pledged to strive to limit in the 2015 Paris Agreement. Scientists suggest that such impacts could be triggering a climate “tipping point,” where devastating changes in the climate system will be locked in, such as the irreversible collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet, which would contribute up to 3 meters to global sea level rise. As shown in the graphic below, the negative Antarctic Sea ice anomaly has widened to a historic gap in 2023, as the ice reached its lowest level on record in June 2023, compared to the period’s long-term average.

Figure 8 –Antarctic Sea Anomalies 1979-2023

Source: Zachary Labe, Princeton University and NOAA GFDL.

The future economic cost is also expected to be large. The disruption of agricultural production and supply chains can lead to increased food prices, affecting both local and global markets. Inflation could spike, making basic necessities less affordable for vulnerable populations. Industries reliant on stable weather conditions, such as construction, energy, and tourism, might experience downturns, leading to job losses and reduced economic growth. The total economic loss is expected to reach $84 trillion over the course of the century, as climate change continues to intensify the strength and increase the frequency of El Niño events.

Time to Panic? (No, but…)

While climate change poses a catastrophic crisis, it is not an apocalypse. At least, not yet.

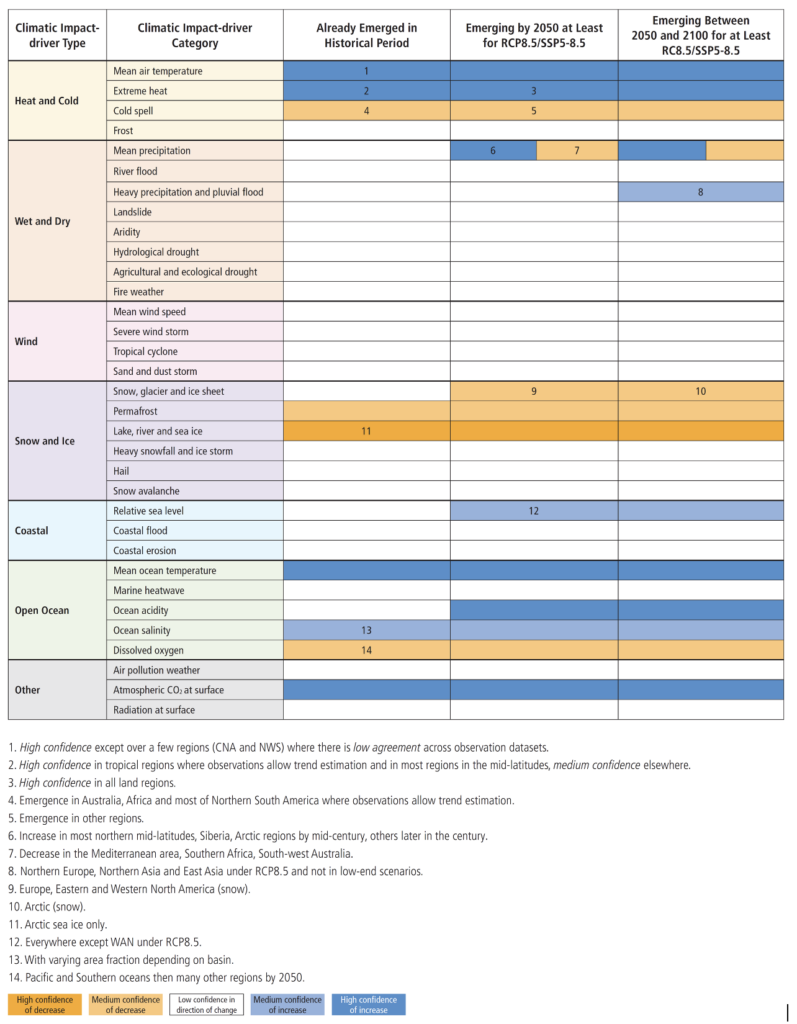

Indeed, caution and adequate preparation, rather than panic, are necessary. According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), there is certainly high confidence that “an increase in heat extremes has emerged or will emerge in the coming three decades in most land regions.” Nevertheless, despite recent trends in a few regions, there is low confidence that other extreme climate signals (e.g., floods, heavy precipitation, droughts, cyclones, storms, etc.) have emerged beyond natural variability. Moreover, the emergence of such climate change signals beyond natural variability is not even expected by 2100, with the only exceptions being heavy precipitation and pluvial floods emerging with only medium confidence.

The table below summarizes the range of extreme climate events, as per the IPCC report, indicating whether they have already emerged or are likely to emerge by 2050 or 2100, with medium or high confidence. White cells indicate that the signal has not yet or is not expected to emerge (low confidence). Blue and orange cells indicate the emergence of respectively increasing and decreasing signals, with medium (lighter color) or high (darker color) confidence levels.

Figure 9 – Emergence of Climate Impact Drivers in Different Time Periods

Source: United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Options?

As we delve into the intricate web of El Niño’s effects on our world, it increasingly becomes evident that this climatic phenomenon holds the power to reshape landscapes, economies, and societies. The 2023 El Niño event, looming as one of the strongest on record, serves as a clarion call for global cooperation and preparedness in the face of climate-related challenges. While uncertainties surround the extent of its impact, history offers us valuable lessons on how to navigate the complexities of El Niño and build a resilient future.

Learning from the Past:

The pages of history bear the imprints of past El Niño events that have left indelible marks on societies. The crises and disruptions caused by these events have spurred advancements in climate science, meteorology, and disaster management. Lessons learned from previous El Niño occurrences have equipped us with tools to anticipate, monitor, and respond to the intricacies of this climatic phenomenon.

A Call for Adaptive Governance:

The fluid nature of El Niño’s impacts necessitates adaptive governance structures that can swiftly respond to changing conditions. National and international policies should be designed with flexibility to address the diverse challenges posed by extreme weather events. This includes investing in early warning systems, disaster preparedness plans, and sustainable resource management. For businesses, adaptation is critical and understanding the impact of weather on supply chain, energy resources and plant/office locations must be assessed.

Collaboration on a Global Scale:

El Niño’s reach knows no borders, emphasizing the importance of global collaboration. Nations, organizations, and communities must unite to share knowledge, resources, and best practices in mitigating the consequences of El Niño. Collaborative efforts can facilitate the rapid exchange of information, enhancing the effectiveness of response and recovery initiatives.

Building Resilience at All Levels:

Resilience lies at the heart of confronting the uncertainties that El Niño presents. Communities must be empowered with the knowledge and tools to adapt to changing conditions, diversify livelihoods, and protect critical infrastructure. Governments can play a pivotal role by investing in climate-resilient agriculture, disaster-resistant construction, and social safety nets that safeguard vulnerable populations.

Investing in Climate Science and Forecasting:

Advancements in climate science have significantly improved our understanding of El Niño, enabling more accurate forecasts. Continued investment in research and technological innovation can refine climate models, enhance predictive capabilities, and provide timely information to inform decision-making. Accessible and reliable climate information empowers societies to plan and respond effectively.

Rethinking Development and Sustainability:

El Niño’s disruptions prompt a reevaluation of development practices and sustainability strategies. From urban planning to water resource management, the potential impacts of El Niño must be integrated into long-term strategies. Embracing sustainable practices, such as water conservation, renewable energy adoption, and ecosystem restoration, can mitigate the vulnerabilities exposed by El Niño events.

Navigating El Niño & Climate Adaptation

Following the recent extreme rises in temperature across the world, and the declaration of El Niño event in June, all eyes are on how much more heat the world will be able to handle. With increasing frequency and intensity of storms, droughts, floods, and wildfires across regions, global food systems, ecosystems, energy systems supply chains, infrastructure, and industrial production are all challenged by the devastating impacts. All this continues to threaten food security, curtail production, and push inflation up. Evidence suggests that while being in a catastrophic crisis, the World is still not ending. We still have time to act to mitigate the impacts of global warming and prepare for the worst. However, it’s either we act now or never, according to the IPCC.

In May 2023, Petteri Taalasthe, the WMO Secretary-General, warned that the declaration of an El Niño event is “the signal to governments around the world to mobilize preparations to limit the impacts on our health, our ecosystems and our economies… Early warnings and anticipatory action of extreme weather events associated with this major climate phenomenon are vital to save lives and livelihoods.”

While climate mitigation is extremely crucial to slow down the trajectory of climate change and prevent more and more extreme events across the globe, preparedness through adaptation is more critical than ever. Both climate mitigation and adaptation are equally important and time-sensitive. We cannot do one and ignore the other. “While emissions reductions remain the most effective means to blunt the economically catastrophic impacts of anthropogenic warming, our findings simultaneously raise the priority of climate adaptation and resilience efforts,” A recent study stated. “Improved disaster risk management could reduce ENSO-driven damages by making economies more resilient to their devastating impacts.”

As overwhelming events such as El Niño intensify, more government action should be expected on all fronts. As stated by Friederike Otto, a scientist at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change in London, “As long as we keep burning fossil fuels we will see more and more of these extremes… I don’t think there’s any stronger evidence that any science has ever presented for a scientific question.”

El Niño, with its intricate dance of oceanic and atmospheric forces, offers a glimpse into the awe-inspiring complexity of our planet’s climate system. The 2023 El Niño event presents both challenges and opportunities for humanity. By drawing on the lessons of the past, fostering resilience, and investing in sustainable practices, we can navigate the uncertain waters of El Niño and forge a path toward a more resilient, adaptive, and stable future. The story of El Niño is an integral part of the broader narrative of humanity’s relationship with the natural world, reminding us of our capacity to learn, innovate, and thrive in the face of adversity.